A Guide to: Natural Wine

By: Brent Nakano

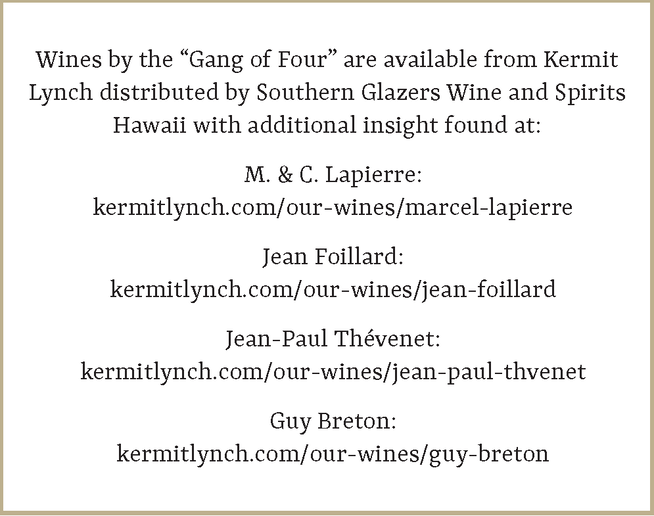

Natural Wine refers to a winemaking philosophy that can be summed up or is occasionally interchanged with “lowintervention wine”. While the term is contemporary, the approach to the technique is more akin to the hundreds of years old winemaking techniques that pre-date the acute understanding and utilization of chemistry and biology to produce a consistent and cost-efficient product. This is not to say that Natural Wine production is simple. Greater attention to detail is required to achieve high quality results without the aid of using modern biology and chemistry to fine-tune flavors. For this reason, Natural Wine is susceptible to more “faults”, particularly that of high volatile acidity from increased levels of acetic acid (vinegar). In an insightful overview of the Natural Wine movement, Alonso González et al. (2022) describes its beginnings in Beaujolais, France during the 1970s. Inspired by the works of winemaker and wine négociant (trader) Jules Chauvet, the Morgon region winemakers Marcel Lapierre, Jean Foillard, Jean-Paul Thévenet, and Guy Breton, started producing and marketing wine that advocated not using herbicides or pesticides in vineyards, not chaptalizing, fermenting with ambient yeasts, and vinifying without SO2.

Kermit Lynch dubbed them the “Gang of Four”. By the 2000s, the movement had gained momentum and winemaker associations had formed, first in France and then in Italy, Spain, elsewhere in Europe, and beyond [1]. This, according to the Monty Waldin in the Oxford Companion to Wine, was a push-back on “the over oaked, over extracted, over technologically manipulated Blockbuster Wines in fashion around the turn of the 20th century, and an implicit challenge to a contemporary wine industry it sees as increasingly additive-prone yet lazily content with legislative status quo imposing less than rigorous labeling requirements for the several hundred potential processing aids, agents, and additives available to winemakers” [2]. Over the past five years, an increase in Google searches and regular articles in Bon Appétit [3], Food and Wine Magazine [4], The New York Times, and Vox [5] show how the method has become more mainstream in America. Alonso González (2022) additionally notes that studies have shown that consumers acquainted with Natural Wine are willing to pay more for it in some contexts [1].

Kermit Lynch dubbed them the “Gang of Four”. By the 2000s, the movement had gained momentum and winemaker associations had formed, first in France and then in Italy, Spain, elsewhere in Europe, and beyond [1]. This, according to the Monty Waldin in the Oxford Companion to Wine, was a push-back on “the over oaked, over extracted, over technologically manipulated Blockbuster Wines in fashion around the turn of the 20th century, and an implicit challenge to a contemporary wine industry it sees as increasingly additive-prone yet lazily content with legislative status quo imposing less than rigorous labeling requirements for the several hundred potential processing aids, agents, and additives available to winemakers” [2]. Over the past five years, an increase in Google searches and regular articles in Bon Appétit [3], Food and Wine Magazine [4], The New York Times, and Vox [5] show how the method has become more mainstream in America. Alonso González (2022) additionally notes that studies have shown that consumers acquainted with Natural Wine are willing to pay more for it in some contexts [1].

Production Practices

While the various natural wine organizations have different specifications,

common rules include:

common rules include:

|

Vineyard involvement and ownership

Some Natural Wine organizations require the involvement of the winemaker in the growing the grapes, either in the form of owning the vineyard from which the grapes are made or regular vineyard work. If this is the case, a person who both grows the grapes and makes the wine may be referred to as a winegrower. Selection Massale (Massal Selection) This French term refers to the propagation of new plantings from old vines already on or near the property. This technique assumes that the genetic material (old vine budwood that is grafted onto rootstock) from vines already flourishing in the environment will produce better wine than clones propagated in an unrelated nursery. It is also through to help to preserve the vineyard’s clonal variation and therefore its terroir. This can be contrasted with clonal selection, in which the genetic material is obtained from a nursery and developed in a way to ensure it was disease free. For more perspective on the usage of Selection Massale: Cole, K. (2018, August 6). Overturning American Winemakers’ Monoclonal Status Quo. SevenFifty Daily. daily.sevenfifty.com/overturning-the-monoclonal-status-quo/ |

Certified Organic Viticulture or

Certified Biodynamic Viticulture The most common practice by both Natural Wine organizations, and Natural Wine producers is the usage of Certified Organic or Biodynamically grown grapes. Organic Viticulture, while certified by different private entities, is regulated by governmental statutes which vary by country. For example, it is specified in the United States by US Code of Federal Regulations § 205.601 and the European Union by Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 and Regulation (EU) No 203/2012. "Biodynamic®” is a trademark and certification mark of “Demeter®”, a private organization which assures consumers that the product has been certified to a uniform standard. While both strategies focus on the use of non-synthetic pesticides (insecticides, herbicides and fungicides), Biodynamic certification can be viewed as an extension of organic agriculture with fewer exceptions, an emphasis on biodiversity, a reduced dependence on imported materials for fertility and pest control, and special preparations [6]. These similarities and differences and their impacts on the vineyard compared to conventional methods will be discussed in a future article. |

|

Common Organic and Biodynamic Practices

• Elemental Sulfur (in liquid or powder form) to combat powdery mildew. • Copper sulfide to treat downy mildew (and indirectly botrytis). • Mechanical methods for weed control. • Fertilization using: • Digested stalks and skins of grapes from organic vines. • “Green manure”, which is the practice of plowing nitrogen rich plants into the soil. Differences: Biodynamic Preparations While there are specific chemicals that are permissible in Organic Agriculture, a main difference and distinguishing feature of Biodynamic agriculture is the requirement for nine preparations to be made from herbs, mineral substances, and animal manures that are utilized in field sprays and compost inoculants applied in minute doses. Originally described by Rudolf Steiner in a series of lectures on agriculture, these Biodynamic preparations are numbered 500 to 508. Ideally, Biodynamic preparations are made on the farm where they are to be used, however, they can be purchased. The following are the Biodynamic preparations as noted by the Demeter Farm Standard and edited for conciseness [7]. |

Preparation 500

Materials: Sheath Raw cow horn from bovine species, fresh cow manure from bovine species that resides on a farm using Biodynamic or organic practices at a minimum. Processing: Manure is packed into the horn as tightly as possible. In the fall it is buried at 18-32 inches deep (adjust to local conditions) in a well drained site with good soil, good humus content, and biological activity. The horns remain in the ground through the duration of the winter then the completely transformed colloidal humus material is removed from the horn. Preparation 501 Material: Raw cow horn from bovine species and quartz (silicon dioxide, feldspar, orthoclase, minerals of high silicon dioxide content). Process: Silica is ground into a fine mealy powder, mixed with water to the consistency of a very thin dough, then placed into the horn. It is then buried in Spring for the duration of the summer. The finished product is stored in a sunny location. |

|

Preparation 502

Materials: Stag bladder (male deer or elk species), yarrow flowers (Achillea millefolium) freshly picked from a farm using Biodynamic, organic practices or “wild crafted” (yarrow flowers dried and moistened with the juice or infusion of yarrow leaves are acceptable). Process: The yarrow is lightly compressed then enclosed into the bladder by tying it shut. It is then hung-up outside in the sun where it stays through the duration of the summer. In autumn it is taken down and buried "not too deeply" in the ground (adjusting for local conditions) where it spends the winter. This means the yarrow flowers should be enclosed for a full year. After digging up the bladder, only the yarrow blossoms should be harvested, and the surrounding material avoided. The yarrow should have transformed into a humus-like material though some of the original florets may still be identifiable. The material is then stored for usage. Preparation 504 Materials: The aerial portion of stinging nettles (perennial, Urtica dioica) from a farm using biodynamic, organic practices or wild crafted that are separated from the surrounding soil so that the harvested preparation does not have surrounding soil mixed in. Process: The nettles are gathered, wilted slightly, lightly compressed and then buried in living topsoil. There it spends the winter and the following summer. After being buried for a whole year, it is dug up. Only the buried nettle is harvested, and it should have transformed towards dark-colored, colloidal humus material. The material is then stored for usage. Preparation 505 Materials: The skull of a domestic animal (cow, goat, or pig), and crumbled oak bark of the Quercus species. |

Process: The bark is chopped into a crumblike

consistency, put into the skull’s brain cavity, and enclosed with natural material (bone, wood, clay, etc.). In the fall it is buried into watery (mucky) earth where water can flow in and out, and remains there over winter. After winter, the oak bark is removed from the skull cavity where it should have transformed towards humus material. The material is then stored for usage. Preparation 506 Materials: A bovine mesentery (peritoneum) and yellow heads of dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) which can be dried in the shade then stored properly until needed. Process: The dandelion blossoms are packed together, sewed (or wrapped) in the bovine mesentery, then buried in earth during autumn. It remains buried through the winter then is dug-up in spring. The blossoms should have transformed towards earthy smelling humus material. The material is then stored for usage. Preparation 507 Materials: Valerian blossoms (Valeriana officinalis) or other local "wild crafted" species of biodynamic quality, preferably organic and "wild crafted" at a minimum. Process: The majority of the plants should have open flowers making for a minimal amount of stem material. Juice or ferment the blossoms the same day as picking to create valerian juice with a distinctive, pungent valerian aroma. Preparation 508 Materials: Field horsetail (Equisetum arvense) fresh or dried in the shade to maintain a vibrant green color. Process: For 508 liquid preparation, prepare a tea or concentrated decoction. This preparation does not need to be buried, as it is a kind of liquid manure once brewed. The preparation is then stored. |

Harvest

Hand harvesting is typical.

Winemaking

Natural Wine has more restrictions compared to Certified Organic Wine or Biodynamic

wine. This is where the term “low intervention wine” comes into play, as Organic and

Biodynamic wines allow for some processes like fining, filtration and addition of Sulfur

Dioxide (SO2) if made in accordance to European Union Organic and Biodynamic wine

standards whereas the U.S. Certified Organic program does not allow its usage. Natural

Wine, however, takes a more hands-off approach.

Fermentation

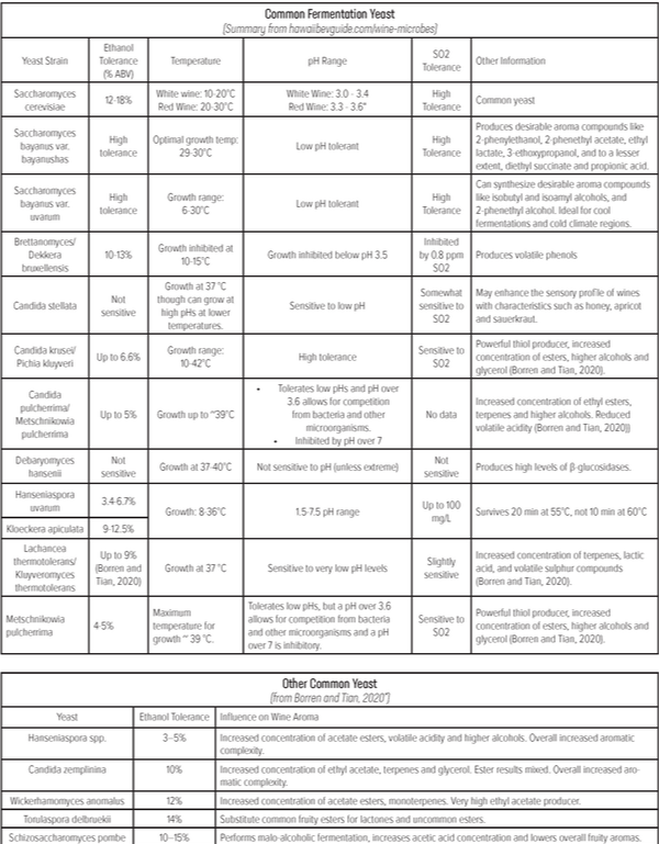

The usage of native yeast is a typical requirement for Natural Wine. As noted in multiple

studies including Bokulich et al (2016) [8] and Coller et al (2019) [9], microbial populations

can be unique to terroir, with slight variations caused by factors like the vintage and

when in the ripening process the grapes were harvested. These variations in microbes result

in distinct metabolites in the final wine and can provide aromatic complexity. The

fermentation process can be performed in two ways: Spontaneous fermentation or inoculation

with a pied de cuve.

Hand harvesting is typical.

Winemaking

Natural Wine has more restrictions compared to Certified Organic Wine or Biodynamic

wine. This is where the term “low intervention wine” comes into play, as Organic and

Biodynamic wines allow for some processes like fining, filtration and addition of Sulfur

Dioxide (SO2) if made in accordance to European Union Organic and Biodynamic wine

standards whereas the U.S. Certified Organic program does not allow its usage. Natural

Wine, however, takes a more hands-off approach.

Fermentation

The usage of native yeast is a typical requirement for Natural Wine. As noted in multiple

studies including Bokulich et al (2016) [8] and Coller et al (2019) [9], microbial populations

can be unique to terroir, with slight variations caused by factors like the vintage and

when in the ripening process the grapes were harvested. These variations in microbes result

in distinct metabolites in the final wine and can provide aromatic complexity. The

fermentation process can be performed in two ways: Spontaneous fermentation or inoculation

with a pied de cuve.

|

Spontaneous fermentation is the process of microbes developing on their own, then

performing fermentation. In wine, this will typically involve different species of bacteria and yeast which are dependent on pH, temperature, and ethanol concentration. Typical microbial growth in spontaneous fermentation is: 1. Non-Saccharomyces yeasts and bacteria start the fermentation. 2. As ethanol concentration increases to ~3% ABV, these die off. 3. Saccharomyces species (particularly Saccharomyces cerevisiae) takes over. Some strains can tolerate up to 18% ABV. Pied dec cuvée inoculations utilize the understanding of microbial development during spontaneous fermentation to select for Saccharomyces yeast. In this process, a portion of ripe grapes are picked before the main harvest and then are spontaneously fermented to a stage where Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other primary fermenters are dominant. The resulting pied de cuvée is used to inoculate the main fermentation vessel. This can help to lessen the impact of potentially undesirable yeast strains that create high concentrations of off-flavors like volatile acidity. |

For more on wine microbial development

during spontaneous fermentations: Hawaii Beverage Guide’s overview article on wine microbes: hawaiibevguide.com/ wine-microbes.html Liu D, Zhang P, Chen D and Howell K (2019) From the Vineyard to the Winery: How Microbial Ecology Drives Regional Distinctiveness of Wine. Front. Microbiol. 10:2679. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02679 I S Pretorius, Tasting the terroir of wine yeast innovation, FEMS Yeast Research, Volume 20, Issue 1, February 2020, foz084, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsyr/foz084 Borren E, Tian B. The Important Contribution of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts to the Aroma Complexity of Wine: A Review. Foods. 2021; 10(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010013 |

Enological Additives

Typically, enological additives are not used in the creation of Natural Wine. This approach

to winemaking has varying degrees of influence because “imperfections” or

"faults" caused by grapes cannot be corrected. For this reason, well made Natural

Wine requires high quality grapes that are damage/disease-free and have ideal sugar/

phenolic ripeness. For economic reasons including the increased amounts of physical

labor for quality viticulture and increased rejection of grapes due to damage,

prices are typically higher than a conventional wine of equivalent quality. Common

additions used in conventional winemaking that are not typically permissible in Natural

Wine:

Acidity corrections, beyond their direct impact on a wine’s flavor, the pH and Total

Acidity of the wine influence which particular microbes grow, the aroma compounds

the microbes produce, the wine’s color, its solubility for tartrates, and its aging potential.

Lower pH (more acidic), is conducive to Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains, whereas

higher pH is more conducive to Candida yeast and bacterial fermenters including

acetic acid bacteria. Yeast nutrition like YAN (yeast assimilable

nitrogen), vitamins, and minerals are typically used to prevent stuck fermentations.

If this occurs, the wine will be microbially unstable. This instability can cause an undesired

secondary fermentation (rather than one purposefully performed), increases

in volatile acidity, and decreases in higher alcohols and esters.

Typically, enological additives are not used in the creation of Natural Wine. This approach

to winemaking has varying degrees of influence because “imperfections” or

"faults" caused by grapes cannot be corrected. For this reason, well made Natural

Wine requires high quality grapes that are damage/disease-free and have ideal sugar/

phenolic ripeness. For economic reasons including the increased amounts of physical

labor for quality viticulture and increased rejection of grapes due to damage,

prices are typically higher than a conventional wine of equivalent quality. Common

additions used in conventional winemaking that are not typically permissible in Natural

Wine:

Acidity corrections, beyond their direct impact on a wine’s flavor, the pH and Total

Acidity of the wine influence which particular microbes grow, the aroma compounds

the microbes produce, the wine’s color, its solubility for tartrates, and its aging potential.

Lower pH (more acidic), is conducive to Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains, whereas

higher pH is more conducive to Candida yeast and bacterial fermenters including

acetic acid bacteria. Yeast nutrition like YAN (yeast assimilable

nitrogen), vitamins, and minerals are typically used to prevent stuck fermentations.

If this occurs, the wine will be microbially unstable. This instability can cause an undesired

secondary fermentation (rather than one purposefully performed), increases

in volatile acidity, and decreases in higher alcohols and esters.

|

Enological tannins

including wood chips are typically not allowed. While not universally used in conventional winemaking, these directly contribute smaller tannins which then polymerize with others to create the more desirable Procyanidins (condensed tannins), pyranoanthocyanins, and pigmented tannins. For more on enological tannins read our article on Wine Polyphenols (hawaiibevguide.com/wine-polyphenols. html) For additional insight into common enological additives and why they are used: Wine Alcoholic Fermentation – Chemical Environment hawaiibevguide.com/wine fermentationchemical-environment.html Physical modification To minimize chemical usage SO2, physical controls are typically used in both conventional and organic winemaking, while Biodynamic winemaking has limitations. Natural Wine, however, may also forgo the following common physical techniques to control microbial growth. |

Fermentation temperature

control is typically used, however some winemakers including those in ViniVeri reject the practice. While this is fine for wineries, with low ambient temperatures during the part of the year which wine is being vinified, it may be restrictive to warmer winegrowing regions and lead to losses in aromatic compounds like esters as well as undesirable microbial growth. Oxygen control through micro-oxidation and hyperoxidation are specifically restricted by some winemakers like those in L'Association des Vins Naturels, and may be restricted as part of a “no physical intervention” clause by others. As these techniques are not always used in conventional winemaking, the impact is stylistic. For additional insight into common manipulations of the wine fermentation environment read our article: Wine Alcoholic Fermentation – Physical Environment: hawaiibevguide.com/wine-alcoholic-fermentation-physical- environment.html |

*Borren E, Tian B. The Important Contribution of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts to the Aroma

Complexity of Wine: A Review. Foods. 2021; 10(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010013

Complexity of Wine: A Review. Foods. 2021; 10(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010013

Stabilization and Filtration

Stabilization of tartrates by chill filtration minimally impacts the flavor of the final

wine, as tartrate crystals are visual “faults” with no impact on the wine’s flavor.

Stabilization by protein fining may impact the wine by adsorbing flavor molecules and

also unwanted bitter flavors.

Filtration is typically not used as this is believed by some Natural Wine producers to

strip out desirable and complex aromas. In conventional wine, sterile filtration, especially

of white wines, is used to minimize sulfur dioxide usage while maintaining microbial stability.

Ethanol reduction techniques like reverse osmosis are typically not used to make natural

wine. While this can be used in conventional winemaking to help balance the alcohol while

allowing for full phenolic ripeness, the usage of spontaneous fermentations for natural

wine will result in a lower ethanol concentration as the yeast that form often do not tolerate

high ethanol environments. This can lead to microbial instability due to the unfermented sugars.

For additional insight into common stabilization and filtration techniques used in wine,

read our article: Post-Fermentation Processes – Stabilization

hawaiibevguide.com/post-fermentation-process-stabilization.html

Stabilization of tartrates by chill filtration minimally impacts the flavor of the final

wine, as tartrate crystals are visual “faults” with no impact on the wine’s flavor.

Stabilization by protein fining may impact the wine by adsorbing flavor molecules and

also unwanted bitter flavors.

Filtration is typically not used as this is believed by some Natural Wine producers to

strip out desirable and complex aromas. In conventional wine, sterile filtration, especially

of white wines, is used to minimize sulfur dioxide usage while maintaining microbial stability.

Ethanol reduction techniques like reverse osmosis are typically not used to make natural

wine. While this can be used in conventional winemaking to help balance the alcohol while

allowing for full phenolic ripeness, the usage of spontaneous fermentations for natural

wine will result in a lower ethanol concentration as the yeast that form often do not tolerate

high ethanol environments. This can lead to microbial instability due to the unfermented sugars.

For additional insight into common stabilization and filtration techniques used in wine,

read our article: Post-Fermentation Processes – Stabilization

hawaiibevguide.com/post-fermentation-process-stabilization.html

|

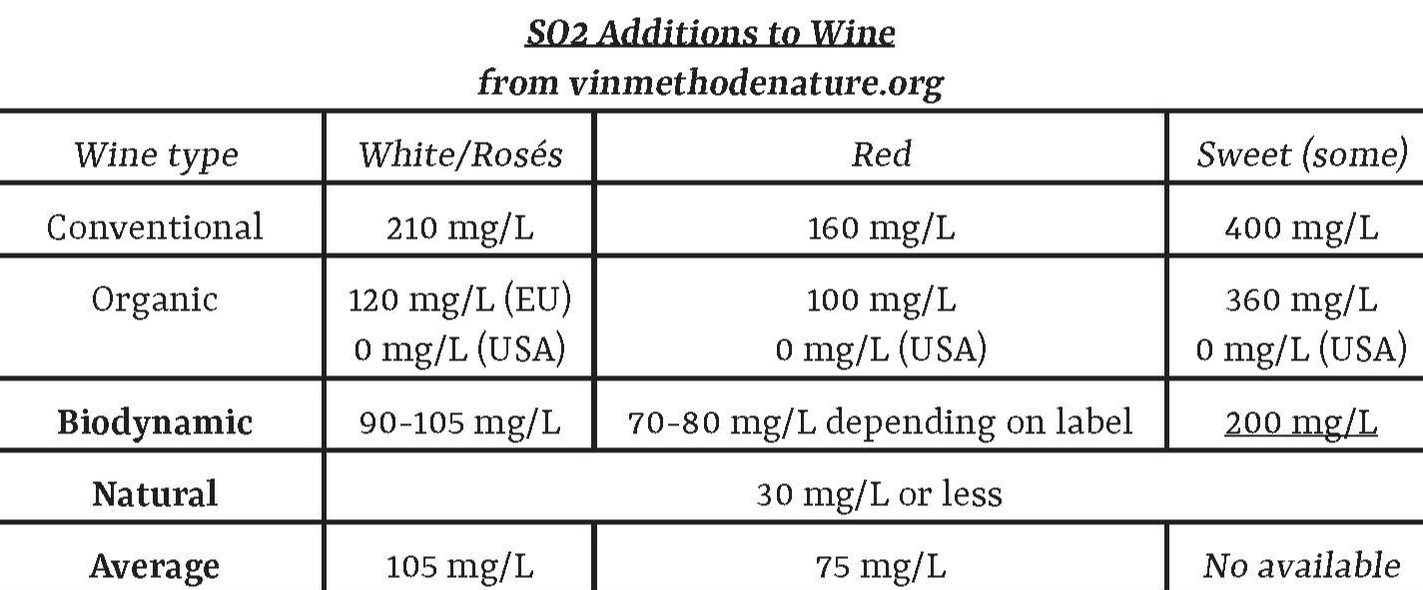

Sulfite usage

Though sulfites occur naturally in wine, natural winemakers have different opinions towards the utilization of sulfur dioxide as an antioxidant and anti-microbial in their wine. WSET in an article on Natural wine notes “however many argue that using too much can erase the identity of the wine.“ Vin Méthode Nature, for example, has a separate designation and label specifically for wines that use 30 mg/L of sulfites and those that do not use sulfites. The organization notes its rationale as inclusivity as: “. . it allows those who are on the path to truly "natural" wine or "natural" (zero input) not to stay on the side of the road.” For more on post-fermentation usage read the following segments of the following articles: • hawaiibevguide.com/post-fermentation-process-stabilization.html • hawaiibevguide.com/ wine-fermentation-chemical-environment. html#sulfur-dioxide • hawaiibevguide.com/ wine-prefermentation.html |

Challenges with microbial stability and

opened bottles of natural wine The microbial instability of natural wine is not one of safety due to its high ethanol content, but one of flavor. This particularly occurs due to acetic acid bacteria oxidizing ethanol to vinegar. In conventional winemaking SO2 is typically used to prevent this, however, other techniques can be used including: • Usage of higher pH (more acidic) grapes, by earlier picking, as fewer non-Saccharomyces microbes survive in that environment. • Ultra-cleanliness in the winery to minimize microbial growth on surfaces and to reduce the populations of acetic acid bacteria carrying fruit flies. • Temperature of 15°C (59°F) inhibits bacteria while still allowing yeast growth and fermentation. • Oxygen can be minimized by the utilization of inert glasses. These should be applied to the headspace of fermenters where they can be combined with punch-downs or pumpovers to submerge any acetic acid bacteria into the anaerobic mass of the must. They should also be applied during racking. • Oxygen pick-up during barrel aging can be minimized with frequent topping off of barrels to fill the headspace. • Lab testing can be used to identify microbial issues before their sensory impacts occur. • High tannin wines are less susceptible to microbial spoilage as tannins are antioxidants. • Keeping a bottle cool once it is open. |

|

Styles Associated but not Exclusive to Natural Wine

The following styles are associated with Natural Wine, however they can be made conventionally and unconventionally. Pétillant Naturel abbreviated to ‘Pét-Nat’ (Méthode Ancestrale) • Winemaking: This semi-sparkling wine is made when a wine that has not been completely fermented is then bottled. Unlike méthode traditionnelle aka méthode champenoise, no sugar addition, dosage or sediment/lees removal occurs. Common styles include whites from Chenin Blanc and Rosé from Gamay, Cabernet Franc, and Grolleau. • Why it is associated with Natural Wine: The style is associated with France’s Loire Valley. This is also where many winemakers produce low-intervention, terroir-driven styles. It is also not stabilized, fined or filtered. Montlouis Pétillant Naturel AOC is a poignant example of this style. Orange Wine/Amber Wine • Winemaking: A white grape is fermented with its skins intact as would be common in red wine production. This increases the wine's polyphenols, especially anthocyanins, and skin-derived aromatic compounds. As anthocyanins range from pink to golden to orange, orange wine is not always orange. The technique is traditionally found in wine from the country Georgia where the grapes are fermented in a clay amphora called qvevri. Other regions which traditionally macerate white wine on their skins include: Tokaji Aszu, Eszencia wines, and white port. • Why its associated with Natural Wine: Many wines in this category emulate Qvevri production, a methodology concurrent with Natural Wine practices. |

Glou Glou (pronounced glue-glue)

• Winemaking: This style is named for the onomatopoeic French expression for wine that is quickly poured out of the bottle and what would be pronounced in English as “glug-glug”. It has also been known as Vin de soif (direct translation: thirsty wine) or by the Brits as quaffers or quaffer wine. It is an often red, lowalcohol (~11.5-13%), juice-like, and low in tannins. • Why its associated with Natural wine: Beaujolais is one of the epicenters of the Natural Wine movement. It is also known for its low-alcohol Gamay based wines that are made using carbonic maceration. While these facts about the Beaujolais wine region are unrelated, emulators of the Natural Wine style from Beaujolais have expanded on this concept, even though the style has more to do with a wine's final ABV. Col Fondo (Prosecco) • Winemaking: 85% Glera (Same as DOC Prosecco) undergoes secondary fermentation in bottle with no disgorgement and therefore the wine is bottled on the lees. This results in a frizzante (less fizzy) rather than spumante wine. Col Fondo translates to “with the bottom" which refers to these lees which settle on the bottom of the bottle. • Labeling: Col Fondo or “Rifermentato in Bottiglia” may be on the bottle, though the latter term technically only describes secondary in-bottle fermentation. • Association with natural wine: As this style is not filtered, it has become associated with natural wine. |

Sources and Suggested Reading

1. Alonso González P., Parga Dans E. and Fuentes Fernández

R. (2022) Certification of Natural Wine: Policy Controversies

and Future Prospects. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:875427.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.875427

2. Robinson, J., & Harding, J. (Eds.). (2015). The Oxford companion

to wine. American Chemical Society.

3. Michelman, J. (2022, October 19). Is natural wine losing its

cool factor? Bon Appétit. Retrieved March 16, 2023, from

www.bonappetit.com/story/natural-wine-list-meinklan-gcool

4. Day, A. (2022, June 27). Natural wine 101: An explainer on

low-intervention wine. Food & Wine. Retrieved March 16,

2023, from www.foodandwine.com/wine/what-is-naturalwine

5. Bull, M. (2019, June 10). Natural wine, explained. Vox.

Retrieved March 16, 2023, from www.vox.com/thegoods/

2019/6/10/18650601/natural-wine-sulfites-organic

6. Demeter Association, Inc. BIODYNAMIC® AGRICULTURE

WINE FAQ. (2009, May). Retrieved March 17, 2023, from

https://demeter-usa.org/downloads/Demeter-FAQ-Wine.pdf

7. Demeter Association, Inc. Biodynamic® FARM STANDARD.

(2017, September). Retrieved March 17, 2023, from

demeter-usa.org/downloads/Demeter-Farm-Standard.pdf

8. Demeter Association, Inc. Biodynamic®PROCESSING STANDARD.

(2017, July). Retrieved March 17, 2023, from demeterusa.

org/downloads/Demeter-Processing-Standards.pdf

9. Bokulich, N. A., Collins, T. S., Masarweh, C., Allen, G., Heymann,

H., Ebeler, S. E., & Mills, D. A. (2016). Associations

among wine grape microbiome, metabolome, and fermentation

behavior suggest microbial contribution to regional

wine characteristics. MBio, 7(3), e00631-16.

https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/mBio.00631-16

10. Global, W. S. E. T. (2023, January 13). What is natural wine?

WSET. Retrieved March 16, 2023, from: wsetglobal.com/

knowledge-centre/blog/2023/january/13/what-is-naturalwine/

11. Coller, E., Cestaro, A., Zanzotti, R. et al. Microbiome of

vineyard soils is shaped by geography and management.

Microbiome 7, 140 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-

0758-7

12. Unesco - Ancient Georgian Traditional Qvevri Wine-Making

method. Intangible Cultural Heritage. (n.d.). Retrieved

March 16, 2023, from https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/ancientgeorgian-

traditional-qvevri-wine-making-method-00870

R. (2022) Certification of Natural Wine: Policy Controversies

and Future Prospects. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:875427.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.875427

2. Robinson, J., & Harding, J. (Eds.). (2015). The Oxford companion

to wine. American Chemical Society.

3. Michelman, J. (2022, October 19). Is natural wine losing its

cool factor? Bon Appétit. Retrieved March 16, 2023, from

www.bonappetit.com/story/natural-wine-list-meinklan-gcool

4. Day, A. (2022, June 27). Natural wine 101: An explainer on

low-intervention wine. Food & Wine. Retrieved March 16,

2023, from www.foodandwine.com/wine/what-is-naturalwine

5. Bull, M. (2019, June 10). Natural wine, explained. Vox.

Retrieved March 16, 2023, from www.vox.com/thegoods/

2019/6/10/18650601/natural-wine-sulfites-organic

6. Demeter Association, Inc. BIODYNAMIC® AGRICULTURE

WINE FAQ. (2009, May). Retrieved March 17, 2023, from

https://demeter-usa.org/downloads/Demeter-FAQ-Wine.pdf

7. Demeter Association, Inc. Biodynamic® FARM STANDARD.

(2017, September). Retrieved March 17, 2023, from

demeter-usa.org/downloads/Demeter-Farm-Standard.pdf

8. Demeter Association, Inc. Biodynamic®PROCESSING STANDARD.

(2017, July). Retrieved March 17, 2023, from demeterusa.

org/downloads/Demeter-Processing-Standards.pdf

9. Bokulich, N. A., Collins, T. S., Masarweh, C., Allen, G., Heymann,

H., Ebeler, S. E., & Mills, D. A. (2016). Associations

among wine grape microbiome, metabolome, and fermentation

behavior suggest microbial contribution to regional

wine characteristics. MBio, 7(3), e00631-16.

https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/mBio.00631-16

10. Global, W. S. E. T. (2023, January 13). What is natural wine?

WSET. Retrieved March 16, 2023, from: wsetglobal.com/

knowledge-centre/blog/2023/january/13/what-is-naturalwine/

11. Coller, E., Cestaro, A., Zanzotti, R. et al. Microbiome of

vineyard soils is shaped by geography and management.

Microbiome 7, 140 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-

0758-7

12. Unesco - Ancient Georgian Traditional Qvevri Wine-Making

method. Intangible Cultural Heritage. (n.d.). Retrieved

March 16, 2023, from https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/ancientgeorgian-

traditional-qvevri-wine-making-method-00870

For more insight into natural wine

Legeron, I. (2018). Natural wine: an introduction to organic and

biodynamic wines made naturally. Ryland Peters & Small. A book

review can be found at: https://wine-economics.org/wp-content/

uploads/2023/02/03-Vol-17-Issue-04-Book-Review-Isabelle-

Legeron-Natural-Wine-An-Introduction-to-Organic-and-Biodynamic-

Wines-Made-Naturally.-Reviewed-by-Kevin-Visconti.pdf

Legeron, I. (2018). Natural wine: an introduction to organic and

biodynamic wines made naturally. Ryland Peters & Small. A book

review can be found at: https://wine-economics.org/wp-content/

uploads/2023/02/03-Vol-17-Issue-04-Book-Review-Isabelle-

Legeron-Natural-Wine-An-Introduction-to-Organic-and-Biodynamic-

Wines-Made-Naturally.-Reviewed-by-Kevin-Visconti.pdf

Published by Hawai'i Beverage Guide