A Guide to Beer

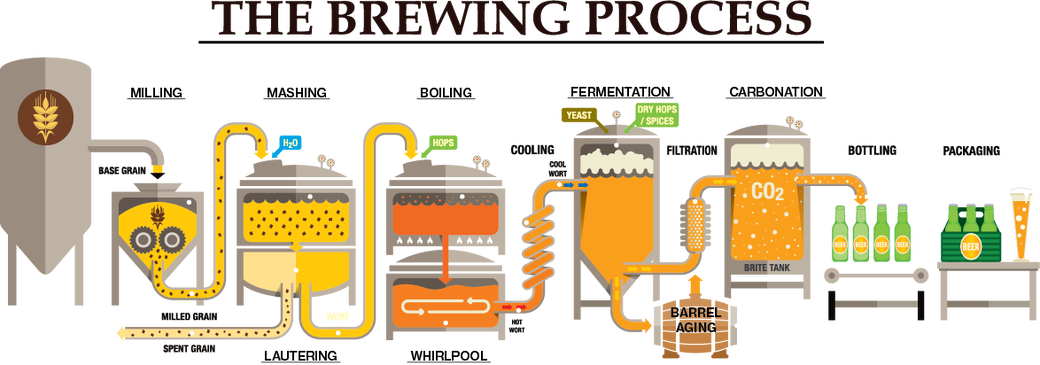

Beer has been brewed for the past 13,000 years. Archaeological evidence form a Natufian burial site at Raqefet Cave, Israel dating back from 13,700–11,700 cal BP shows a brew of wheat or barley, oats, legumes and bast fibers (including flax) that were packed in fiber-made containers and stored in boulder mortars.1 Overtime, beer has been refined as brewers’ knowledge of the biological factors that influence the flavor of beer has increased. This understanding has also led to the development of different styles of beer which vary by the ingredients and production techniques. For example, in the 16th century, hops replaced an herbal mixture called gruit. This change is noted in the historical record as the Reinheitsgebot, also known as the German Purity Law of 1516. This law defines beer’s ingredients as: Malted Barley, Yeast, Hops and Water. Another large leap in beer development was the confirmation of microbial fermentation in 1876 by Louis Pasteur. Most recently the DNA analysis and chemical analysis of yeast and hops have led to major developments in understanding flavor.

1Liu, Li & Wang, Jiajing & Rosenberg, Danny & Lengyel, György & Nadel, Dani.

(2018). Fermented beverage and food storage in 13,000 y-old stone mortars at

Raqefet Cave, Israel: Investigating Natufian ritual feasting. Journal of Archaeological

Science: Reports. 21. 783-793.

1Liu, Li & Wang, Jiajing & Rosenberg, Danny & Lengyel, György & Nadel, Dani.

(2018). Fermented beverage and food storage in 13,000 y-old stone mortars at

Raqefet Cave, Israel: Investigating Natufian ritual feasting. Journal of Archaeological

Science: Reports. 21. 783-793.