|

|

Distillery Address

66-542 Haleiwa Rd, Haleiwa, HI 96712 *Entrance is on Paalaa Rd Private Tours Only Contact: [email protected] https://kaloimo.exblog.jp Blog is in Japanese, use Google Translate for English |

Hawaii is full of traditions inspired from Japan’s Meiji Restoration Period (1868 to 1912) and Taisho Periods (1912 to 1926) as these traditions were brought over by Japanese immigrants to Hawaii’s plantations. These include New Year’s celebrated with ahi, soba and ozoni along with a variety of other food, and the Bon Dances during Obon Season. Even Shirokiya, founded in August 1662 in Edo, Japan, only exists in Hawaii. Hawaii Shochu Company, though relatively new, continues the legacy of traditional Japanese practices through the making of Honkaku Shochu in Wailua, Oahu on land that once was worked by Japanese immigrants over 100 years ago.

According to Ken Hirata, founder and owner of Hawaii Shochu Company: “I think Hawaii is the right place to do things because we (in Japan) are losing the importance of Japanese traditions. We [in Japan] don’t have as many Bon dances as Hawaii anymore and we don’t celebrate much. We don’t eat that much maguro (ahi) on New Year’s either. I think it’s beautiful to keep that type of tradition alive.”

According to Ken Hirata, founder and owner of Hawaii Shochu Company: “I think Hawaii is the right place to do things because we (in Japan) are losing the importance of Japanese traditions. We [in Japan] don’t have as many Bon dances as Hawaii anymore and we don’t celebrate much. We don’t eat that much maguro (ahi) on New Year’s either. I think it’s beautiful to keep that type of tradition alive.”

-

Founding Story

-

People

-

Why Imo (Sweet Potato) Shochu

-

Hawaii's Influence

<

>

“While visiting Hawaii when I was about 25 years old, which was 25 years ago, I was eating poi and thought: Poi is like a fermented food from taro; if they have something like this in Hawaii, maybe I can make shochu. At that time, I was just joking with my friends because I didn’t know anything about making shochu, but the idea came back maybe 15 years later and I thought: It would be fun to make shochu in Hawaii.”

To learn shochu-making, Hirata-san persistently asked to apprentice with Mr. Toshihiro Manzen of Manzen Shuzo Co. in Kagoshima, Japan. Mr. Manzen was hesitant as this style of traditional shochu-making is typically passed down through the generations. However, after drinks at a bar and conversation with Mr. Manzen about his plans to make shochu in Hawaii, Mr. Manzen gave in. This led to a three-year long apprenticeship.

“I really loved his shochu; the way he makes shochu is different because he applies Japan’s traditional handcrafted shochu-making techniques. These days, a majority of the shochu or sake makers are equipped with the automated koji-making machines. My sensei (teacher) still makes koji by hand (the traditional way) in a koji room. We also use ceramic pots for fermentation. Then, the still is a traditional Japanese wooden still not so many people use anymore. We use those traditional, old-style equipment and tools and we also apply handcrafted koji-making techniques.”

I really loved his shochu; the way he makes shochu is different because he applies Japan’s traditional handcrafted shochu-making techniques. These days, a majority of the shochu or sake makers are equipped with the automated koji-making machines. My sensei (teacher) still makes koji by hand (the traditional way) in a koji room. We also use ceramic pots for fermentation. Then, the still is a traditional Japanese wooden still not so many people

To learn shochu-making, Hirata-san persistently asked to apprentice with Mr. Toshihiro Manzen of Manzen Shuzo Co. in Kagoshima, Japan. Mr. Manzen was hesitant as this style of traditional shochu-making is typically passed down through the generations. However, after drinks at a bar and conversation with Mr. Manzen about his plans to make shochu in Hawaii, Mr. Manzen gave in. This led to a three-year long apprenticeship.

“I really loved his shochu; the way he makes shochu is different because he applies Japan’s traditional handcrafted shochu-making techniques. These days, a majority of the shochu or sake makers are equipped with the automated koji-making machines. My sensei (teacher) still makes koji by hand (the traditional way) in a koji room. We also use ceramic pots for fermentation. Then, the still is a traditional Japanese wooden still not so many people use anymore. We use those traditional, old-style equipment and tools and we also apply handcrafted koji-making techniques.”

I really loved his shochu; the way he makes shochu is different because he applies Japan’s traditional handcrafted shochu-making techniques. These days, a majority of the shochu or sake makers are equipped with the automated koji-making machines. My sensei (teacher) still makes koji by hand (the traditional way) in a koji room. We also use ceramic pots for fermentation. Then, the still is a traditional Japanese wooden still not so many people

Ken Hirata and his wife Yumiko are the only two employees of their company. According to Hirata-san: “We like the way we are right now. The production volume is very small, but this is the max we can do right now. Fortunately, people have been really supportive, so we are able to sell out everything we make. This business doesn’t make us rich, but we are doing okay enough to live on and have a nice life in Hale’iwa.

According to Hirata-san: “Kagoshima, located on the southern part of Kyushu Island, is the center of sweet potato shochu-making in Japan. Within Kagoshima Prefecture, there are more than ninety sweet potato shochu distilleries. The climate is warm and you can find lots of sweet potatoes there. There are similarities between Kagoshima and Hawaii: warm climate, availability of sweet potatoes, and soil influenced by volcanic activities. Those similarities, I thought, would give a positive influence on shochu-making.”

Hawaii Shochu Company makes a product heavily influenced by the terroir of the state that goes beyond locally sourced sweet potato. Hirata-san said, “because we apply the traditional handcrafted method of shochu-making, we try to make it as natural as possible, leaving it to nature. All the elements of Hawaii, including water, wild yeast, and things you cannot see or feel, influence the taste, flavor and aroma of shochu.”

Ingredients

Twelve distillation runs, consisting of 200 lbs of koji and 1000 lbs of sweet potatoes, are made before bottling. In all, 12,000 pounds of sweet potatoes and 2400 pounds of rice are used. It takes two months to fill the tank in which the shochu will rest. This results in approximately 3,000 bottles per batch.

-

Rice

-

Sweet Potato (Imo)

-

Water

-

Koji

<

>

2400 lbs of Koji rice are used per batch

Koda Farms Kokuho Rose Brand Heirloom Rice is used to make the koji rice. According to Hirata-san: “We wanted to make shochu from ingredients as local as possible. The closest place [for growing rice] is California because no rice is grown in Hawaii at a commercial level.” This particular rice was chosen because “it is their highest quality of rice. We did research on what type of rice we can use and where to buy it from. Because we are immigrants from Japan, like Koda who came to the United States over 100 years ago and founded Koda Farms, we felt a connection. Then, just like the name of the rice, Heirloom, they have been passing its importance from generation to generation.

Unfortunately, not many shochu makers in Japan care about the quality of rice, but my sensei really cares about the quality of the rice. I thought it would be good to use high-quality rice even though it’s not really the main ingredient.”

Koda Farms Kokuho Rose Brand Heirloom Rice is used to make the koji rice. According to Hirata-san: “We wanted to make shochu from ingredients as local as possible. The closest place [for growing rice] is California because no rice is grown in Hawaii at a commercial level.” This particular rice was chosen because “it is their highest quality of rice. We did research on what type of rice we can use and where to buy it from. Because we are immigrants from Japan, like Koda who came to the United States over 100 years ago and founded Koda Farms, we felt a connection. Then, just like the name of the rice, Heirloom, they have been passing its importance from generation to generation.

Unfortunately, not many shochu makers in Japan care about the quality of rice, but my sensei really cares about the quality of the rice. I thought it would be good to use high-quality rice even though it’s not really the main ingredient.”

12000 lbs of sweet potatoes are used per batch

Purple sweet potatoes of different varieties are most commonly used for making Hawaii Shochu Company shochu. Hirata-san said: “According to the University of Hawaii, about 30 varieties of sweet potatoes are grown in Hawaii. Every one of our batches is different. Our most current batch, Number 12, we call Molokai blend because the sweet potatoes we used are mainly from L&R Farms (landrfarms.com) on Molokai. The one [batch] we just made, which will be ready this fall, will be called Maui blend because the majority of the sweet potatoes we used for that batch came from the island of Maui.”

Different varieties of sweet potatoes and the production site of the sweet potatoes change, and it influences the taste. Hawaii Shochu Company uses multiple farm partners because of limitations in sourcing. According to Hirata-san: “We don't get to pick [the sweet potatoes] much; it's more the farmers. They call us and they say, "Hey, we've got some sweet potatoes. Are you interested?" I go, "Okay, ship me some samples and we’ll try them. If they’re good, I just buy." We're not a big company, so we don't really buy much. We buy whatever is available, or whatever we can find that time, so it's more like they [the farmers] pick us.”

The differences in flavors between the sweet potatoes affect the final flavors of the distillate. Hirata-san said: “The Molokai sweet potatoes were dark purple (the skin is also purple), and the sugar content was a little high; that made the shochu dryer compared to the two [batches] from before. Those [batches] that used the sweet potatoes from the North Shore were more like the Okinawan sweet potatoes and had a higher water content, so they were not as sweet as the Molokai blend. The North Shore batch didn't come out that dry, but the aroma was different. Each sweet potato has uniqueness and distinct characteristics. If it's [sweet potato] grown in the summertime, it's dryer because there’s not much rain in the summer; but if it's grown in the wintertime, it has more moisture because of the rain. That makes a difference. It's like the grapes to the wine, but it’s not as distinctive as brewed alcoholic beverages because we distill the potatoes.”

Purple sweet potatoes of different varieties are most commonly used for making Hawaii Shochu Company shochu. Hirata-san said: “According to the University of Hawaii, about 30 varieties of sweet potatoes are grown in Hawaii. Every one of our batches is different. Our most current batch, Number 12, we call Molokai blend because the sweet potatoes we used are mainly from L&R Farms (landrfarms.com) on Molokai. The one [batch] we just made, which will be ready this fall, will be called Maui blend because the majority of the sweet potatoes we used for that batch came from the island of Maui.”

Different varieties of sweet potatoes and the production site of the sweet potatoes change, and it influences the taste. Hawaii Shochu Company uses multiple farm partners because of limitations in sourcing. According to Hirata-san: “We don't get to pick [the sweet potatoes] much; it's more the farmers. They call us and they say, "Hey, we've got some sweet potatoes. Are you interested?" I go, "Okay, ship me some samples and we’ll try them. If they’re good, I just buy." We're not a big company, so we don't really buy much. We buy whatever is available, or whatever we can find that time, so it's more like they [the farmers] pick us.”

The differences in flavors between the sweet potatoes affect the final flavors of the distillate. Hirata-san said: “The Molokai sweet potatoes were dark purple (the skin is also purple), and the sugar content was a little high; that made the shochu dryer compared to the two [batches] from before. Those [batches] that used the sweet potatoes from the North Shore were more like the Okinawan sweet potatoes and had a higher water content, so they were not as sweet as the Molokai blend. The North Shore batch didn't come out that dry, but the aroma was different. Each sweet potato has uniqueness and distinct characteristics. If it's [sweet potato] grown in the summertime, it's dryer because there’s not much rain in the summer; but if it's grown in the wintertime, it has more moisture because of the rain. That makes a difference. It's like the grapes to the wine, but it’s not as distinctive as brewed alcoholic beverages because we distill the potatoes.”

“We just use the water available. This land is leased by Kamehameha Schools. They have wells. We try to go as natural as possible. Of course we use clean water, but nothing fancy.” Said Hirata-san.

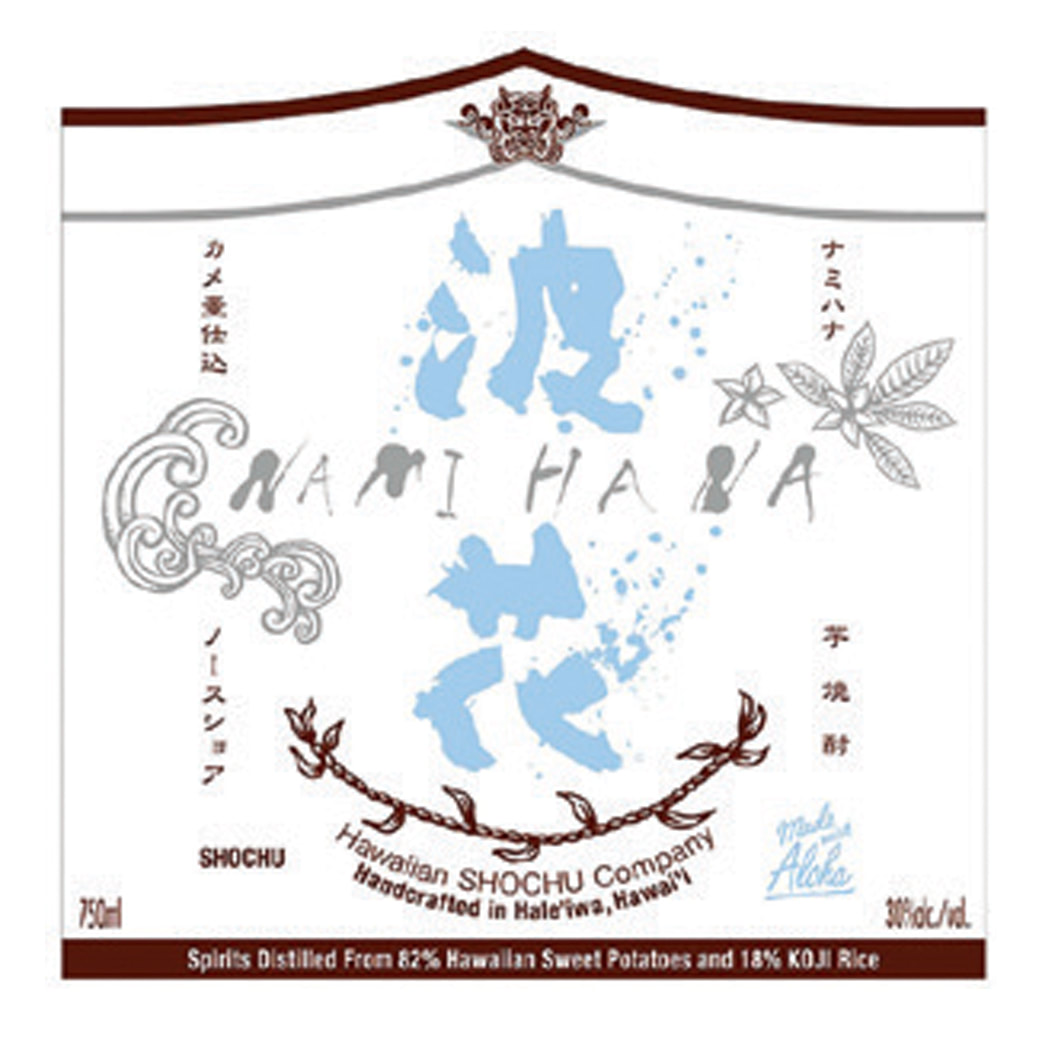

Hawaii Shochu Company typically uses black koji for their regular Namihana bottles. According to Hirata-san: “We use black koji from a certain koji-maker; it’s different from my sensei’s koji. I think it’s just a personal preference. I believe that particular koji pairs well with Hawaii sweet potatoes and Hawaii’s type of climate.”

White koji is occasionally used in the limited edition bottles. However, Hawaii Shochu Company has no concrete rules for when white or black kojji is used except for not to mix black and wite koji. This is because one usually dominates. According to Hirata-san: “Sometimes, the black one pairs well with one type of sweet potato and the white one pairs better with a different type of sweet potato. There are so many things you can do with the combinations of koji and sweet potatoes. However, Hawaii is too warm for the yellow sweet potatoes. The yellow one is usually used for the sake brewing process where a really low fermentation temperature is maintained. For the shochu-making process, the fermentation temperature is high, so we can do it here naturally.”

To source the koji, fresh starter is purchased from Japanese koji-makers for every new batch. According to Hirata-san: “There are koji-makers in Japan because miso-makers, shoyu-makers, and sake-makers all need koji. The koji-makers supply the starters to those vendors and they have over a thousand years of history.”

White koji is occasionally used in the limited edition bottles. However, Hawaii Shochu Company has no concrete rules for when white or black kojji is used except for not to mix black and wite koji. This is because one usually dominates. According to Hirata-san: “Sometimes, the black one pairs well with one type of sweet potato and the white one pairs better with a different type of sweet potato. There are so many things you can do with the combinations of koji and sweet potatoes. However, Hawaii is too warm for the yellow sweet potatoes. The yellow one is usually used for the sake brewing process where a really low fermentation temperature is maintained. For the shochu-making process, the fermentation temperature is high, so we can do it here naturally.”

To source the koji, fresh starter is purchased from Japanese koji-makers for every new batch. According to Hirata-san: “There are koji-makers in Japan because miso-makers, shoyu-makers, and sake-makers all need koji. The koji-makers supply the starters to those vendors and they have over a thousand years of history.”

Fermentation

-

Koji Making

-

Fermentation

-

Sweet potato preparation

-

Niji (Second) Shikomi

<

>

|

“Hawaii is warm enough to make koji naturally. We aim for 82 to 88 [degrees Fahrenheit], so there is no need to have an AC device or any air controlling device. In that respect, Hawaii is a good place to make koji.” Said Hirata-san.

The koji making process starts with making koji rice in a koji room. At Hawaii Shochu Company, this process takes two nights, or approximately 48 hours in which, according to Hirata-san, “We have to go in and do all kinds of stuff every three to four hours. The first step is washing [the rice] then steaming the rice in a traditional wooden steamer. Next, the rice is brought to the koji room where a handful of koji is sprinkled over 200 lbs of rice and then massaged into it. After massaging the koji into the rice, the rice is divided into small wooden trays. Not so many people in Japan use these [koji rooms and wooden rice cookers] anymore. They have nice koji-making machines.” |

To tell when the koji rice is complete, according to Hirata-san, “it’s by the visual, texture and smell all combined. It’s just like how you can tell if something is molded; there’s a fluffy, hairy thing around the rice. But it’s a good mold, so it smells really nice and sweet, and of course, you can eat it. It’s supposed to be healthy for your body.”

|

Ichiji (First) Shikomi

After the koji rice is complete, it is mixed with water and yeast in clay fermentation pots and fermented for a week. According to Hirata-san: “My master gave them [the pots] to us, so they all came from Kawashima, Japan, and are about 150 years old. You cannot replace them.” Trays of koji rice are all combined into one pot and then water and yeast is added. |

After one week, black koji makes the ferment look dark, while white koji is plain white and the alcohol content is around 10%. According to Hirata-san: “If you drink this, the taste is similar to unrefined sake because only the koji is fermented or brewed.”

Hirata-san also noted: “The important thing is that we use both koji and yeast. Both of them play a different role during the fermentation process.”

Hirata-san also noted: “The important thing is that we use both koji and yeast. Both of them play a different role during the fermentation process.”

While waiting for the first shikomi, the sweet potatoes are cleaned and the unwanted parts of the potatoes are removed before they are steamed.

After steaming the sweet potatoes, they are mixed with the fermented koji rice. This mash, also known as moromi, is then fermented for another eight to ten days. At this stage, alcohol content becomes around 15% before heading to distillation.

Distillation/ Resting/ Aging

-

Still Story

-

Distillation

-

Resting

-

Bonzai Series

<

>

|

The Still is a Japanese cyprus or “sugi,” which was built by an artisan in Japan. According to Hirata-san: “I think sugi doesn’t give much flavor to it. It has a natural flavor and it can withstand against the heat; it doesn’t bend much. If you use a different type of wood, it’s not suitable to work with high temperatures.” Wooden stills are rare in Japan’s shochu industry as well. According to Hirata-san: “Not so many people in Japan use this [wooden still] anymore. Usually, they have a big, nice, modern factory still and next to it is a small display still they sometimes use for events. [However] my sensei uses wooden stills only, so I follow in his step.” The unique wooden still also has been a point of interest to many distillers and craft spirits enthusiasts. According to Hirata-san: “The still is the one thing mainland whiskey makers and vodka makers (visiting us) get very interested in. Not many people have seen wooden stills.”

|

You can definitely tell the difference between wooden and stainless steel stills. Even though the wooden still completely seals, it still breathes. That makes the spirits softer and lessens the harshness. It’s kind of a slow and soft distillation process compared to the, high-tech or modern stills. However, it’s humbug because you have to replace the still every 13 years because it doesn’t last as long as its metal counterpart.

The still is heated by passing water through a series of two water heaters to create a soft steam, which is then piped into the still to heat the moromi.

The still is heated by passing water through a series of two water heaters to create a soft steam, which is then piped into the still to heat the moromi.

The second shikomi passes through the still only once. In this process, after the moromi is heated with steam and the alcohol evaporates, the condensed alcohol is collected in a second tank. According to Hirata-san: “From one distillation with that much materials [200 lbs rice and 1000 lbs sweet potato], we can collect shochu for maybe 200 liters (52 gallons). Then, we repeat this process until we fill up the tank. That takes about two months and [in the end] we use 12,000 to 15,000 pounds of sweet potatoes.

The shochu rests between four and five months, which is why it takes approximately six months to make a batch. As there is only one resting tank, the batch size is limited to 3,000 bottles.

The Bonzai Series is experimental and often isn’t traditional shochu, but a modern take on it. According to Hirata-san: “We play with the Banzai series, and every Banzai has different characteristics; the aroma is especially different from the ones from Japan.” This, in the past release, have included shochu co-fermented with pineapple.

To age some of the Bonzai Series, Mizunara Oak wood pieces, similar to barrel staves, are steeped in the shochu. The Mizunara wood vary based on how it was charred. For example, in one batch, the Mizunara was charred by burning strawberry-guava wood from Hawaii. In this non-traditional product series, Hirata-san is very experimental. The strawberry-guava wood charred Mizunara was inspired by the idea of wanting to use both Japan wood and Hawaii wood together. “Two years ago, we used kiawe to smoke Mizunara. Because we charred heavier with kiawe,the Mizunara was smokier, I think. The strawberry-guava wood is sweeter because we didn’t char the wood for very long.” Other projects in the Banzai Series have included: Sweet potato shochu, which has a uniqueness and distinct characteristics. I think it’s a beautiful flavor and we’re so lucky to do this in Hawaii.

To age some of the Bonzai Series, Mizunara Oak wood pieces, similar to barrel staves, are steeped in the shochu. The Mizunara wood vary based on how it was charred. For example, in one batch, the Mizunara was charred by burning strawberry-guava wood from Hawaii. In this non-traditional product series, Hirata-san is very experimental. The strawberry-guava wood charred Mizunara was inspired by the idea of wanting to use both Japan wood and Hawaii wood together. “Two years ago, we used kiawe to smoke Mizunara. Because we charred heavier with kiawe,the Mizunara was smokier, I think. The strawberry-guava wood is sweeter because we didn’t char the wood for very long.” Other projects in the Banzai Series have included: Sweet potato shochu, which has a uniqueness and distinct characteristics. I think it’s a beautiful flavor and we’re so lucky to do this in Hawaii.

Availability

Releases are made twice a year: once in the spring and once in the fall.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed