Sake is Japan’s national beverage. In fact it is also known as nihonshu, which translates to Japanese Liquor. There are various styles of sake, yet instead of style names, sake uses a series of descriptors relating to the different parts of its production process. Therefore, learning the

names of the various production processes is essential to understanding sake. To equate it to the wine world, a style on the bottle would read: “Cabernet Sauvignon, whole cluster fermented, oak aged, cold filtered, with no sulfites added.”

names of the various production processes is essential to understanding sake. To equate it to the wine world, a style on the bottle would read: “Cabernet Sauvignon, whole cluster fermented, oak aged, cold filtered, with no sulfites added.”

Legal Definition

Article 3 of Japan's Liquor Tax Act

"'Sake' refers to any of the following alcoholic beverages with an alcohol content of less than 22%:

"'Sake' refers to any of the following alcoholic beverages with an alcohol content of less than 22%:

- The filtered product of fermenting rice, koji rice and water;

- The filtered product of fermenting rice, kojirice, water, sakekasu and other items specified in regulations (the total weight of such other items specified in regulations must not exceed 50% of the total weight of rice, including rice for making koji rice);

- The filtered product of adding sakekasu to sake."

History

|

Sake’s origins are thought to be in China, even though China has no current history of sake production. The earliest documentation of sake production is found in the third-century Chinese history books, which states “the Japanese have a taste for sake and are in the habit of gathering to drink sake when mourning the dead.” (Comprehensive Guide to Japanese Sake).

From the 10th century to the 15th century, sake was typically consumed for ceremonial purposes being that in the 10th century, it was mainly brewed at the Imperial Court. Also, from the 12-15th century, sake was predominantly brewed at Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. The middle ages (12th -15th century) brought advancements in brewing technology. This period began the implementation of using lactic acid fermentation, shubo and yeast as well as the origination of morohaku sake or sake made from 100% polished rice. Sometime between the 15th and 16th centuries, additional advancements were made which included the usage of hi-ire (pasteurization). The most significant technological advancement was the ability to make 1600 Liter vats, which facilitated the mass production of sake by those non-affiliated with temples or shrines. |

During the Edo period (17th Century), sake brewing grew to 38,000 kiloliters at the beginning of the 18th century. This was equivalent to an annual per-capita

consumption of 54 liters. During this period, the ratio of water to polished rice was approximately half of its current percentage, suggesting that predominantly sweet, heavy sake were consumed. It was not until the 19th century that sake started to resemble what it does now with cool fermentation temperatures and similar ingredient proportions. The significant leap during this period was due to the influence of European scholars who started scientific research on sake. This eventually resulted in the founding of the National Research Institute of Brewing. The more recent developments in sake brewing are related to the Ginjo styles of sake which only became possible when the modern vertical rice-polishing machine was developed around 1930. At first these were limited to competition sake. It was not until the 1980’s that the technology (and the required brewing techniques) became widespread enough to support the Niigata “Ginjo Boom” (1986 and 1991). For more sake history watch WSET's A History of Sake with Natsuki Kikuya on Youtube: youtu.be/WqcYxSFvdZc |

Geographical Regions

-

Approach to Regions

-

Key Geographical Regions

<

>

Sake style, from a regionality perspective, is based upon the following historical generalizations:

• The type of rice traditionally grown in the region.

• The hardness of water from the natural springs of the region.

• The fermentation temperature, which corresponded to the ambient

temperature due to a lack of temperature control.

• The brewing techniques practiced by the local toji guild (brewers guild).

• The type of rice traditionally grown in the region.

• The hardness of water from the natural springs of the region.

• The fermentation temperature, which corresponded to the ambient

temperature due to a lack of temperature control.

• The brewing techniques practiced by the local toji guild (brewers guild).

GI Requirements are typically

Hyogo Prefecture

The Federation of Hyogo Prefecture Brewers Associations:

hyogo-sake.or.jp/en/

Hyogo has been the largest sake production region since the 18th century. It contains two Geographical Indication (GI) Regions: Nadagogo and Harima.

Subregions

GI Nadagogo

GI Harima

Yamagata Prefecture and GI

Fushimi (Kyoto Prefecture)

Niigata Prefecture

Niigata Sake Brewers Association: niigata-sake.or.jp/en/

Niigata prefecture is the third largest sake production region and has the most number of sake breweries. It is also Japan’s largest rice growing region of both table and sake rice. The Niigata is known for its Tanrei Karakuchi style. It's light dry, pure, clean with a clean kire finish.

Ishikawa Prefecture

Subregion

Hakusan GI

www.sake-hakusan.info/

For more insight from Japan’s National Tax Agency: www.nta.go.jp/english/taxes/liquor_administration/02_06.htm

Hiroshima Prefecture

sake-hiroshima.com/en/

Primary rice: Hattannishiki, Senbonnishiki

Water: Very soft water

Toji Guilds: Hiroshima Toji

- Rice: Domestically produced rice

- Water: Water shall be collected within the GI.

Hyogo Prefecture

The Federation of Hyogo Prefecture Brewers Associations:

hyogo-sake.or.jp/en/

Hyogo has been the largest sake production region since the 18th century. It contains two Geographical Indication (GI) Regions: Nadagogo and Harima.

- Primary rice: Yamada-nishiki

- Water: Miya-mizu (Water from the gods)

- Primary Toji Guilds: Tamba Toji, Nanbu Toji and Echigo Toji

- Style: Otoko-zake

Subregions

GI Nadagogo

- Official Website: nadagogo.ne.jp/

- GI Requirements: nta.go.jp/english/taxes/liquor_administration/02_08.htm

GI Harima

- GI Requirements: nta.go.jp/english/taxes/liquor_administration/02_09.htm

Yamagata Prefecture and GI

- Official Website: yamagata-sake.or.jp/

- GI Requirements: nta.go.jp/english/taxes/liquor_administration/02_3.htm

- Ingredents

- Primary rice: Yamagata Prefecture grows rice which can bear special labeling.

- Dewa 33 (出羽33), Dewasansan (San=3)

To be labeled Dewa 33, the sake shall be a Junmai Ginjo grade milled to a minimum of 55% and use Yamagata yeast and koji. - Yuki Megami” 雪女神 “Snow Goddess"

To be labeled Yuki Megami, the sake shall be a Daiginjo or Junmai Daiginjo made with rice milled to a minimum of 50%.

Fushimi (Kyoto Prefecture)

- Kyoto Sake Brewers Association: kyotosake.jp/en/

- Fushimi is the major sake producing region of Kyoto, and the 2nd largest sake production area.

- Ingredients

- Primary rice: Iwai

- Water: Soft water compared to Hyogo

- Toji guilds: Tango Toji

Niigata Prefecture

Niigata Sake Brewers Association: niigata-sake.or.jp/en/

Niigata prefecture is the third largest sake production region and has the most number of sake breweries. It is also Japan’s largest rice growing region of both table and sake rice. The Niigata is known for its Tanrei Karakuchi style. It's light dry, pure, clean with a clean kire finish.

- Primary rice: Gohyakumangoku

Ishikawa Prefecture

- Ishikawa Sake Brewers Association: ishikawa-sake.jp/eng/

- Primary rice: Gohyakumangoku

- Water: Soft to semi-hard

- Primary Toji Guild: Noto Toji

Subregion

Hakusan GI

www.sake-hakusan.info/

For more insight from Japan’s National Tax Agency: www.nta.go.jp/english/taxes/liquor_administration/02_06.htm

Hiroshima Prefecture

sake-hiroshima.com/en/

Primary rice: Hattannishiki, Senbonnishiki

Water: Very soft water

Toji Guilds: Hiroshima Toji

Ingredients

-

Rice

-

Koji

-

Yeast

-

Water

<

>

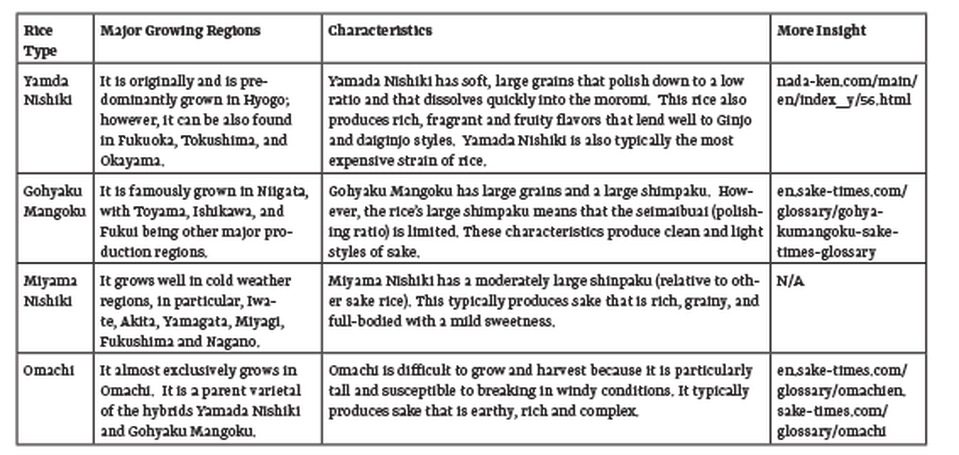

Sake is made from fermented, non-glutinous Japonica rice. Though lower yielding than table rice, the different varietals of sakamai are coveted because they contain less protein than table rice, most of their starch resides in a well-defined center, and their large-grains are less likely to crack when polished.

Types of rice

There are two common types of Asian Rice: Long grain Indica

(jasmine and basmati) and medium-grain Japonica (Japanese style rice). There are two general classifications of Japonica’s substyles: Glutinous rice with 80% more Amylopectin, and non-glutinous rice. Non-glutinous Japonica rice is typically used to make sake. Of the styles of non-glutinous rice, there is table rice and sake specific rice. Due to scarcity, most sake is made from table rice, whereas sake-specific rice is only used in premium sake making.

(jasmine and basmati) and medium-grain Japonica (Japanese style rice). There are two general classifications of Japonica’s substyles: Glutinous rice with 80% more Amylopectin, and non-glutinous rice. Non-glutinous Japonica rice is typically used to make sake. Of the styles of non-glutinous rice, there is table rice and sake specific rice. Due to scarcity, most sake is made from table rice, whereas sake-specific rice is only used in premium sake making.

Types of Sake Rice

Of the varietals of sake rice:

• Okute, is planted and harvested late and has large grains that produce full-bodied sake.

• Wase is planted and harvested early because it grows in colder climate areas. The rice terms of wase and okute are typically not used on labels, but rather specific varietals are cited.

• Okute, is planted and harvested late and has large grains that produce full-bodied sake.

• Wase is planted and harvested early because it grows in colder climate areas. The rice terms of wase and okute are typically not used on labels, but rather specific varietals are cited.

Sake Rice Grades

Sake rice is typically graded by government inspectors before being sold. However, uninspected rice may be used for making Futsu-shu. Sake rice is graded by the following factors:

- Average weight of 1,000 grains (senryuju).

- Percentage of flawed rice. Flawed rice are grains that are broken, cracked or under ripe.

- Moisture content. Too much moisture risks rot, and too little increases the likelihood of cracking during polishing.

Grades of Sake Rice (in descending order):

• Tokujo (Best)

• Tokuto (2nd Best)

• Itto (1st Grade)

• Nitto (2nd Grade)

• Santo (3rd Grade)

• Tokujo (Best)

• Tokuto (2nd Best)

• Itto (1st Grade)

• Nitto (2nd Grade)

• Santo (3rd Grade)

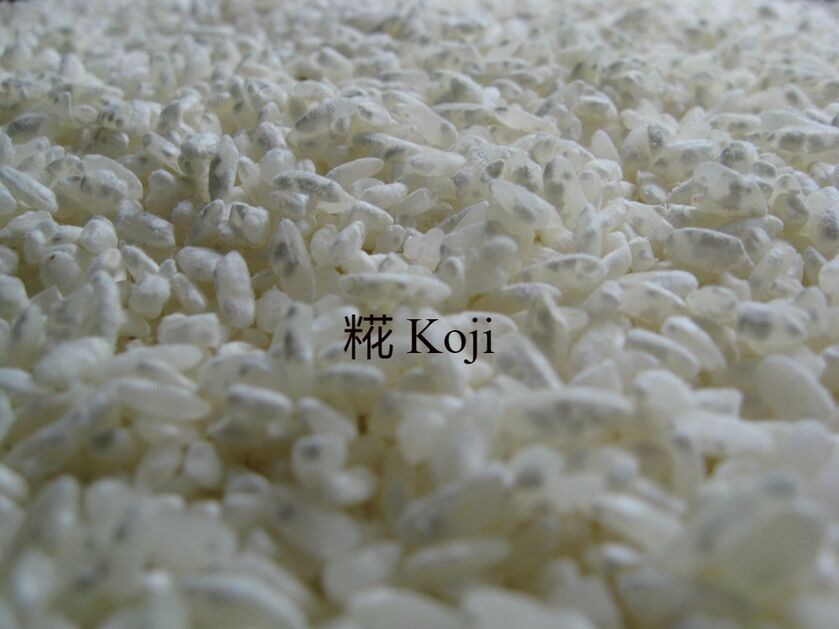

Though yeast yields most of sake’s flavors, Koji (Aspergillus oryzae) produces enzymes which convert starch to sugar in the same way that malted barley provides enzymes for beer. Though malted rice could be used in place of koji for the enzymatic conversion of starches, the flavors from the germ and endosperm are undesirable in sake. The quantity of koji also impacts the speed of yeast propagation, therefore the koji making process is closely monitored to control its growth.

Koji, also provides nutrients, specifically amino acids and peptides, which create a hospitable environment for fermentation by the yeast. These amino acids also contribute to the umami and (very slightly) to the acidity of the sake as well as other subtle aroma/flavour molecules, in particular a chestnut aroma.

Koji, also provides nutrients, specifically amino acids and peptides, which create a hospitable environment for fermentation by the yeast. These amino acids also contribute to the umami and (very slightly) to the acidity of the sake as well as other subtle aroma/flavour molecules, in particular a chestnut aroma.

Types of Koji

Koji Form Factor

Koji Growth Patterns

• So-haze koji covers the entire rice grain and ensures there is a more rapid starch to sugar conversion. This supports a faster and warmer fermentation, and gives more body and flavour to

the final sake.

So-haze koji is ideal for:

• Futsu-shu because it boosts the flavour intensity and compensates

for some of the dilution that occurs when jozo alcohol is added.

• Sake with intense flavours, full body, high acidity and high umami.

• Tsuki-haze koji grows in a lightly spotted pattern around the rice grain and ultimately yields fewer koji being developed on each grain. This means that fewer vitamins and proteins are produced for the yeast resulting in a slower and longer fermentation and thus producing a sake with delicate aromas and a

light texture. Producing this koji style is more difficult than sohaze

koji as the moisture needs to remain low and the amount of koji spores is restricted. Additionally, the koji room is warmer and less humid.

Tsuki-haze is ideal for:

• Ginjo and daiginjo sakes, where purity and delicate texture are desired, together with ginjo aromas, low acidity and low umami.

• Honjozo made with a lean texture and restrained aroma

• Nuri-haze refers to an uneven and excess koji growth pattern.

the final sake.

So-haze koji is ideal for:

• Futsu-shu because it boosts the flavour intensity and compensates

for some of the dilution that occurs when jozo alcohol is added.

• Sake with intense flavours, full body, high acidity and high umami.

• Tsuki-haze koji grows in a lightly spotted pattern around the rice grain and ultimately yields fewer koji being developed on each grain. This means that fewer vitamins and proteins are produced for the yeast resulting in a slower and longer fermentation and thus producing a sake with delicate aromas and a

light texture. Producing this koji style is more difficult than sohaze

koji as the moisture needs to remain low and the amount of koji spores is restricted. Additionally, the koji room is warmer and less humid.

Tsuki-haze is ideal for:

• Ginjo and daiginjo sakes, where purity and delicate texture are desired, together with ginjo aromas, low acidity and low umami.

• Honjozo made with a lean texture and restrained aroma

• Nuri-haze refers to an uneven and excess koji growth pattern.

|

Koji Suppliers

Akita Konno (Japan): akita-konno.co.jp/en/ seihin/01.html Higuchi Moyashi (Japan): higuchi-m.co.jp/english/ Tokushima Seikiku (Japan): iidagroup.co.jp/seikiku_en/ |

Koji Images Provided by:

Higuchi Matsunosuke Shoten Co. Ltd |

Though koji is unique to making sake (and shochu), yeast has the most significant flavor impact of any sake ingredient. Similar to its role in beer, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the same strain as ale yeast and wine yeast, turns sugars into alcohol and aroma and flavor compounds.

Traditionally, sake was made with ambient yeast (natural fermentation) or was made from the foam of a successful fermentation. However, like in beer, “flavor drift” occurs due to yeast mutations. Like in the evolution of beer, advancements in technology have led to the isolation of yeast strains yielding more consistent results. Some kura [breweries] have isolated their own strains to produce unique flavors.

Yeast Characteristics

Sake yeast are Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that can tolerate a high alcohol environment of up to 22% ABV. This is in contrast to wine yeast that typically tops out at 16% ABV. Sake yeast also has a similar fermentation temperature (43-64°F) to that of white wine (45-60°F), and cooler than that of beer (60-75°F).

Sake Aroma Compounds

Common desirable aroma compounds found in sake include:

Undesirable aroma compounds include:

Yeast Characteristics

Sake yeast are Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that can tolerate a high alcohol environment of up to 22% ABV. This is in contrast to wine yeast that typically tops out at 16% ABV. Sake yeast also has a similar fermentation temperature (43-64°F) to that of white wine (45-60°F), and cooler than that of beer (60-75°F).

Sake Aroma Compounds

Common desirable aroma compounds found in sake include:

- Isoamyl Acetate has the aromas of banana and honeydew melon. It is found in higher quantities in Ginjo and Daiginjo sake.

- Ethyl Caproate has the aromas of apple, pineapple and pear.

- Ethyl Acetate, found in Nama-zake, can enhance pineapple notes, but can also smell of nail polish remover.

- Acetaldehyde has notes of fresh cut grass and woody notes. This is also commonly found in Nama-zake.

Undesirable aroma compounds include:

- Diacetyl has a cheesy or buttery smell. It’s commonly found in malolactic fermentation Chardonnay.

- 2-Methoxy-4-Vinylphenol (4VG), produces the fruity and clove notes typically found in Belgain Ales. It is a sign that non-sake yeast were in the ferment.

- For additional insight into sake aroma compounds read:

en.saketimes.com/learn/the-science-of-sake- aroma

Common Sake Yeast

Yeast names, like those in beer, are typically numbered with the name of the source. Some sake yeast are simply known by its origin, for example “Ku-mamoto Kobo.” Yeast strain names con-taining the suffix 01 are foamless. These foamless yeast were developed in the 1970’s, because the typical sake yeast cre-ates a foam that may take up half the fermentation tank. However, there is some debate on if there is a loss of flavor be-tween foaming yeast and non-foaming yeast.

• Kyokai Kobo No. 7 is the most common general purpose sake yeast because of its consistency. It has soft aromas and is used in sake like Junmai and Honjozo.

• Kyokai Kobo No. 9 is a “ginjo” yeast known for its aroma. It originated at the Koro Brewery (Kumamoto Prefecture Brewing Research).

• Kyokai Kobo Yeast No. 1801 is a new strain with a high production of isoamyl acetate and ethyl caproate and Isoamyl alcohol.

Yeast Sources

• Sake Brewers Society’s Kyokai kobo: www.jozo.or.jp/yeast/

• White Labs: whitelabs.com/

Yeast names, like those in beer, are typically numbered with the name of the source. Some sake yeast are simply known by its origin, for example “Ku-mamoto Kobo.” Yeast strain names con-taining the suffix 01 are foamless. These foamless yeast were developed in the 1970’s, because the typical sake yeast cre-ates a foam that may take up half the fermentation tank. However, there is some debate on if there is a loss of flavor be-tween foaming yeast and non-foaming yeast.

• Kyokai Kobo No. 7 is the most common general purpose sake yeast because of its consistency. It has soft aromas and is used in sake like Junmai and Honjozo.

• Kyokai Kobo No. 9 is a “ginjo” yeast known for its aroma. It originated at the Koro Brewery (Kumamoto Prefecture Brewing Research).

• Kyokai Kobo Yeast No. 1801 is a new strain with a high production of isoamyl acetate and ethyl caproate and Isoamyl alcohol.

Yeast Sources

• Sake Brewers Society’s Kyokai kobo: www.jozo.or.jp/yeast/

• White Labs: whitelabs.com/

Sake, like beer, is predominantly water. Water also influences the sake yeast’s rate of development and therefore the sake’s fermentation time.

Ideal sake water

Brewers are allowed to adjust sake water. Reverse osmosis water is commonly used in the brewing process, though not necessarily for all water additions. What makes for ideal sake water (outside of meeting drinking water standards) is water that is:

Famous Water styles

Before adjusting water chemistry was well understood, brewers used the local water. This resulted in regional styles of sake, as the natural mineral content impacted by the yeast propagation. These styles include:

Ideal sake water

Brewers are allowed to adjust sake water. Reverse osmosis water is commonly used in the brewing process, though not necessarily for all water additions. What makes for ideal sake water (outside of meeting drinking water standards) is water that is:

- Low in iron

- High in magnesium, as it increases the metabolism of sugar by the yeast. The water should also contain potassium and phosphorus to assist in providing a stable fermentation and reduce the risk of “contamination” by other inoculants or stuck fermentation. Though calcium is often found in conjunction with magnesium, it is insignificant in sake production.

Famous Water styles

Before adjusting water chemistry was well understood, brewers used the local water. This resulted in regional styles of sake, as the natural mineral content impacted by the yeast propagation. These styles include:

- Miya-mizu water, from Nada in the Kobe prefecture, is mineral rich and yields re-strained and drier styles of sake. It also tends to restrict floral ginjo aromas as the yeast propagates faster and fermentation occurs quicker.

- Fushimi water near Kyoto, relative to Nada water, has fewer minerals. This results in less vigorous fermentation and the softer Kyoto-style sake.

- Otoko-zake/Onano-zake: In general, Otoko, which translates to male, refers to sake made from hard water. Onano, which translates to female, refers to sake made from soft water.

Process

-

Rice Processing

-

Koji Making

-

Shubo/Moto (Fermentation Starter)

-

Moromi

<

>

Rice Processing

Harvest and Sake Brewing Season

Rice is harvested from late summer and into autumn. Traditionally, the brewing season began once the temperatures cooled in the late fall/early winter and lasted until the spring. The duration of the season depends on the sake brewery and their production size. Now the brewing season generally starts around Oct. 1, which is known as World Sake Day. However, as refrigeration technology and brewing technology increase, an increasing amount of breweries are brewing year round. "I'd say it's more common to find breweries not brewing year round right now (2021), although more and more are starting to do it."- Eli Nygren, Sake Specialist

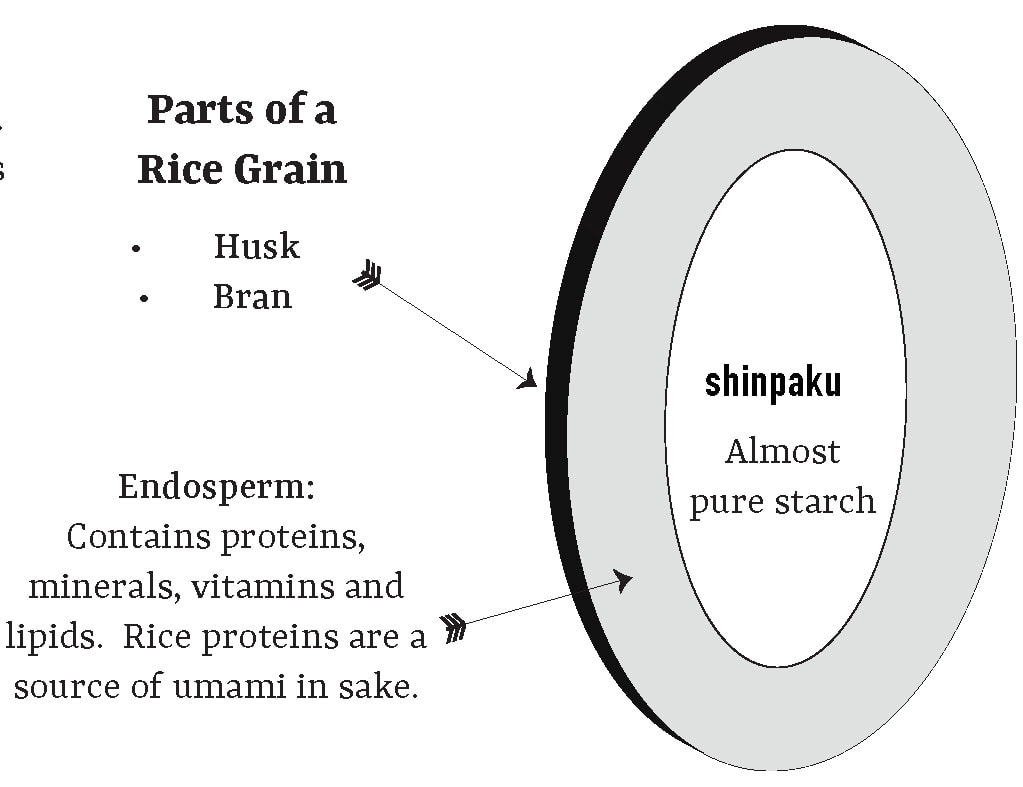

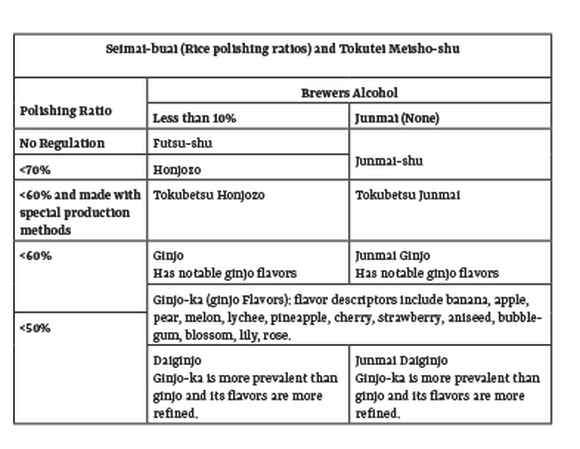

Rice is polished to remove everything, to varying degrees, but the shinpaku.

• Coarsely polished/less highly polished rice is more savory, contains more body, and is more acidic and umami.

• Ginjo and daiginjo polishing ratios create sake that is typically fruitier, lighter in body, lower in acid, and lower in umami than more coarsely polished rice.

• Highly polished rice costs more because it is more labor intensive and there is a loss of product due to only a fraction of the overall grain of rice remaining. However, this does not necessarily mean that the sake is “better” or of "higher quality" as the two products are different. This is akin to adding juniper and other botanicals to vodka, which raises the price; it does not make it better vodka, but rather a completely different product.

• Coarsely polished/less highly polished rice is more savory, contains more body, and is more acidic and umami.

• Ginjo and daiginjo polishing ratios create sake that is typically fruitier, lighter in body, lower in acid, and lower in umami than more coarsely polished rice.

• Highly polished rice costs more because it is more labor intensive and there is a loss of product due to only a fraction of the overall grain of rice remaining. However, this does not necessarily mean that the sake is “better” or of "higher quality" as the two products are different. This is akin to adding juniper and other botanicals to vodka, which raises the price; it does not make it better vodka, but rather a completely different product.

|

Rice Washing Methods

The remaining nuka, (the part of the rice polished off) which clings to the rice after polishing, is either hand washed or washed off by machine. Hand washing rice is a more traditional method and is still used in artisanal batches of sake as it results in a more thorough washing. However, recent technological advancements use fine air bubbles in the water to replicate hand stirring. |

|

|

Rice is soaked

To raise the moisture content from 30 to 35%, the rice is soaked. The ratio of the moisture content is dependent on the type of rice and whether it will be used for koji. Rice with excessive moisture will cause excessive koji growth and/or result in an ex-cessive breakdown in fermentation. If either occurs, proper flavor development will not occur. As an agricultural product with variations between growing seasons, there are no set formulas for rice hydration. The factors that impact the duration of time that rice will be soaked for are:

After soaking, the rice is drained and left to rest between a few hours to overnight (and less than 24 hours) before steaming. |

|

|

Rice is steamed

Steaming rice raises the moisture level within each grain, which changes the structure of the starch and kills any unwanted microorganisms. In the rice steaming process, rice for koji making is hydrated to a lower level than rice used for the sake mash (called kakemai). To achieve this in a traditional steamer, rice furthest from the steam vents, which is typically at the top of the steamer, is used for koji production. Hikikomi (Rice cooling process) The rice is cooled to 90-95°F (32-35°C) in the brewery either on cooling mats in the brewery, or by a cooling machine. Once cooled, rice is laid on a toko or koji table. |

|

Koji Making Process

Temperature and humidity are crucial for koji making, as too much heat will kill the koji and too little will slow koji growth. For this reason, koji is traditionally made in a temperature and climate-controlled koji room. Due to the high humidity, koji room walls were traditionally made of hinoki (Japanese cypress wood), but now the walls are typically made of stainless steel.

• Law requires that 15% of rice used to make premium sake must be koji.

• Koji-making machines were once only used for high volume production; however, improvements in technology have created machines that produce consistent and high quality koji.

• A high quantity of koji creates a faster fermentation with more intense flavors, more acidity, and more umami.

• A lower quantity of koji creates a slower fermentation with lighter flavor, less acidity, and less umami.This is typically used to produce delicate Ginjo styles.

• Law requires that 15% of rice used to make premium sake must be koji.

• Koji-making machines were once only used for high volume production; however, improvements in technology have created machines that produce consistent and high quality koji.

• A high quantity of koji creates a faster fermentation with more intense flavors, more acidity, and more umami.

• A lower quantity of koji creates a slower fermentation with lighter flavor, less acidity, and less umami.This is typically used to produce delicate Ginjo styles.

|

Tanekiri (Inoculating rice with koji)

Koji spores are sprinkled on rice using hand shakers in order to inoculate it, or koji spores are sprayed onto the rice using an automated koji machine. The inoculated rice is then covered for 8-12 hours in blankets to retain warmth and moisture so that the rice, which is at an initial temperature of approximately 86-90 °F (30-32°C) rises to approximately 92-95 °F (33-35°C). |

|

Kirikaeshi (Rebreaking Up)

As koji develops unevenly, clumps of rice are broken up so that the rice is of even temperature. This can either be done by hand, or by the rotating rollers of a koji-making machine. Once the rice is broken up (by hand), it is re-wrapped, and the koji is left to continue to grow for another 8-12 hours. During this phase, the rice temperature is reduced from 92°F (33°C) to approximately 88°F (31°C); it then rises back after a few hours to about 92°F (33°C).

Mori (mounding)

The mori phase develops the koji growth pattern and quantity. For better control, the koji-mai is often transferred to smaller containers. However, instead of filling the container completely, a mound of rice is created. The containers are then regularly rotated around the koji room for even heat in the same way barrels are rotated by some whiskey distilleries. During this process the temperature of the rice reaches approximately 92°F (33°C), and continues to rise to over 95°F (35°C).

The following are the various containers used:

• Toko-koji (Bed-koji)

• Rice is kept on the koji bed.

• Good for Futsu-shu, Honjozo, Junmai and Ginjo. It is unsuitable for Daiginjo.

• Hako-koji (Box Koji)

• 15kg to 40kg of rice is transferred to a hako (box).

• Too labor intensive for futsu-shu and not accurate enough for daiginjo.

• Futa koji (Tray Koji)

• 1.5 to 2.5 kg of rice is transferred to containers called futa. This is optimal for daiginjo sakes.

• Mechanical koji making

• Rice is regularly rotated in this phase. Mechanical koji making has limitations to heat distribution for tsuki-haze.

As koji develops unevenly, clumps of rice are broken up so that the rice is of even temperature. This can either be done by hand, or by the rotating rollers of a koji-making machine. Once the rice is broken up (by hand), it is re-wrapped, and the koji is left to continue to grow for another 8-12 hours. During this phase, the rice temperature is reduced from 92°F (33°C) to approximately 88°F (31°C); it then rises back after a few hours to about 92°F (33°C).

Mori (mounding)

The mori phase develops the koji growth pattern and quantity. For better control, the koji-mai is often transferred to smaller containers. However, instead of filling the container completely, a mound of rice is created. The containers are then regularly rotated around the koji room for even heat in the same way barrels are rotated by some whiskey distilleries. During this process the temperature of the rice reaches approximately 92°F (33°C), and continues to rise to over 95°F (35°C).

The following are the various containers used:

• Toko-koji (Bed-koji)

• Rice is kept on the koji bed.

• Good for Futsu-shu, Honjozo, Junmai and Ginjo. It is unsuitable for Daiginjo.

• Hako-koji (Box Koji)

• 15kg to 40kg of rice is transferred to a hako (box).

• Too labor intensive for futsu-shu and not accurate enough for daiginjo.

• Futa koji (Tray Koji)

• 1.5 to 2.5 kg of rice is transferred to containers called futa. This is optimal for daiginjo sakes.

• Mechanical koji making

• Rice is regularly rotated in this phase. Mechanical koji making has limitations to heat distribution for tsuki-haze.

The next two phases, Naka-shigoto and Shimai-shigoto, are used to reduce the rice exterior’s moisture content. This is especially important for tsuki-haze koji.

Naka-shigoto (middle-work)

At the peak of the koji growth process (approximately 30-33 hours in) the temperature of the rice is lowered from 97°F (36°C) to around 92°F (33°C) so that the koji are not killed. This is done by flattening the koji mound and creating furrows in the rice to increase surface area, allowing heat and water to evaporate from the rice. The temperature, however, will rise back up to about 100°F (38°C) after a period of time.

Shimai-shigoto (Final-work)

To further encourage the koji to grow into the rice rather than only coating the exterior, the rice mound is further flattened. During this phase the temperature of the rice should remain higher than 100°F (38°C) but less than 110°F (43°C). This occurs between 36 to 38 hours into the process.

De-koji (sending-out)

During de-koji, the koji growth is stopped by blowing cool air over the rice. This reduces the temperature from 100°F (38°C) to an ambient temperature; this occurs 44-48 hours into the process.

Naka-shigoto (middle-work)

At the peak of the koji growth process (approximately 30-33 hours in) the temperature of the rice is lowered from 97°F (36°C) to around 92°F (33°C) so that the koji are not killed. This is done by flattening the koji mound and creating furrows in the rice to increase surface area, allowing heat and water to evaporate from the rice. The temperature, however, will rise back up to about 100°F (38°C) after a period of time.

Shimai-shigoto (Final-work)

To further encourage the koji to grow into the rice rather than only coating the exterior, the rice mound is further flattened. During this phase the temperature of the rice should remain higher than 100°F (38°C) but less than 110°F (43°C). This occurs between 36 to 38 hours into the process.

De-koji (sending-out)

During de-koji, the koji growth is stopped by blowing cool air over the rice. This reduces the temperature from 100°F (38°C) to an ambient temperature; this occurs 44-48 hours into the process.

Shubo/Moto

(Fermentation starter)

The goal of the shubo is to create an ideal growth environment for sake yeast propagation and inhibit the growth of unwanted microorganisms. This is done by creating a mini-mash with a higher ratio of koji-mai (30-33% vs 20-23%) than typically found in the moromi (primary fermentation). It should be noted that the kake-mai rice varietal or the polishing ratio may differ from that used for koji-mai because kakemai has no influence on growing koji and is mainly used to contribute starch. There are different styles of making shubo, and the shubo style name may be found in the “name”/style/description of the sake:

Kimoto (生酛)

Kimoto is the traditional method of shubo making. It involves mashing the kake-mai and koji-mai into a paste using wooden poles in a process called yama-oroshi at a temperature of approximately 43-45°F (6-7°C). The belief was that mashing sped up the breakdown of rice and increased the amount of contact between the rice starch and koji enzymes. In this shubo technique, starch-to-sugar conversion takes place before the growth of almost all microorganisms except for nitrate producing bacteria. This production of nitrates before the growth of any other microorganisms helps to create a hospitable environment for lactic acid producing bacteria. This ultimately results in a shubo with a high concentration of sugar and a low pH due to the presence of lactic acid. When combined with a low temperature, it inhibits the growth of undesirable yeast and other spoilage microbes. The Kimoto method results in complex, rich, earthy flavors.

Yamahai (山廃)

Yamahai was introduced in the early 1990’s. It is a simplified version of the Kimoto method in that it skips the step of mashing the koji-mai and kake-mai (yama-oroshi) by adding more water and slightly increasing the temperature. In fact, the full name for Yamahai is “Yama-oroshi haishi”, meaning “discontinuation of Yama-oroshi.” Though faster than the Kimoto method, Yamahai is typically only used in specialty brews where it provides earthy, complex flavors.

Kimoto (生酛)

Kimoto is the traditional method of shubo making. It involves mashing the kake-mai and koji-mai into a paste using wooden poles in a process called yama-oroshi at a temperature of approximately 43-45°F (6-7°C). The belief was that mashing sped up the breakdown of rice and increased the amount of contact between the rice starch and koji enzymes. In this shubo technique, starch-to-sugar conversion takes place before the growth of almost all microorganisms except for nitrate producing bacteria. This production of nitrates before the growth of any other microorganisms helps to create a hospitable environment for lactic acid producing bacteria. This ultimately results in a shubo with a high concentration of sugar and a low pH due to the presence of lactic acid. When combined with a low temperature, it inhibits the growth of undesirable yeast and other spoilage microbes. The Kimoto method results in complex, rich, earthy flavors.

Yamahai (山廃)

Yamahai was introduced in the early 1990’s. It is a simplified version of the Kimoto method in that it skips the step of mashing the koji-mai and kake-mai (yama-oroshi) by adding more water and slightly increasing the temperature. In fact, the full name for Yamahai is “Yama-oroshi haishi”, meaning “discontinuation of Yama-oroshi.” Though faster than the Kimoto method, Yamahai is typically only used in specialty brews where it provides earthy, complex flavors.

Kimoto and Yamahai flavors

Sokujō (速醸), meaning "quick fermentation," is the “modern” (starting in the early 1900’s) method of making shubo. It adds lactic acid to the starter mash, and reduces the overall sake production time from 28 days to 14 days. The Sokujo method also provides better control over the quantity of lactic acid in the sake compared to Yamahai and Kimoto methods, and results in sake with less umami and lighter flavor than Kimoto or Yamahai sake.

Ko-on toka moto

In the Ko-on Toka Moto shubo, high temperatures are used to sterilize the mixture and breakdown starches. This produces a very clean style of sake.

- Kimoto and yamahai sake typically have rich flavors, though analysis does not show any increased levels of amino acids or umami, compared to Sokujo-moto sake.

- Kimoto and Yamahai sake tend to have higher acidity than Sokujo-moto sake, but it would be possible to produce Sokujo-moto sake with more acidity if the producer desired.

- For Yamahai and some Kimoto sake, brewers deliberately aim for complex, nutty and caramel flavors that are derived from the exposure to oxygen. For some fun additional insight into Kimoto and Yamahai

- Flavors: https://sake-world.com/about-sake/types-of-sake/special-sake/

Sokujō (速醸), meaning "quick fermentation," is the “modern” (starting in the early 1900’s) method of making shubo. It adds lactic acid to the starter mash, and reduces the overall sake production time from 28 days to 14 days. The Sokujo method also provides better control over the quantity of lactic acid in the sake compared to Yamahai and Kimoto methods, and results in sake with less umami and lighter flavor than Kimoto or Yamahai sake.

Ko-on toka moto

In the Ko-on Toka Moto shubo, high temperatures are used to sterilize the mixture and breakdown starches. This produces a very clean style of sake.

Moromi

(Primary Fermentation)

Moromi is built in a three step process and results in a fermentation of two parts koji-mai, eight parts kake-mai, and 13 parts water. Sake fermentation is unusually complex because sugar is being produced at the same time as it is being consumed; whereas in other beverages, the producer starts with a fixed amount of sugar.

Hatsu-zoe (First Addition)

The shubo is transferred to a larger tank where approximately 1/6 of the total amount of koji-mai, kake-mai, and water are combined. The temperature at this stage is typically between 54-59°F (12-15°C).

Odori (meaning to dance)

Nothing is added and yeast are allowed to propagate (dance).

Naka-zoe ("Middle")

Double the previous total amount of water, koji and steamed rice are added, so that the total volume at this stage is now about half the final total.

Tome-zoe

The remainder of the water, rice and koji are added. During the middle and final additions, because fermentation is exothermic, if the fermentation tank is not temperature-controlled via a water jacket, some brewers replace some of the added water with ice.

Ending the Fermentation

The temperature is lowered to 31-41 °F (3-5 °C) to stop the fermentation without killing the yeast, as dead yeast can produce off flavors.

- Fermentation temperature ranges from 43-64°F (6°C to 18°C) with the majority of sake being fermented between 54-64°F (12-18°C). Ginjo styles of sake must be fermented at much lower temperature of 50-54°F (around 10-12°C) and takes much longer (30-35 days).

- The ferments produce a liquid of around 17-20% ABV with approximately 15-25 g/L of unfermented residual sugar.

- Fermentation size ranges from less than one metric tonne to more than 30 tonne batches with an ideal size of brewing Ginjo style being between 600 kg to 1500 kg of polished rice per batch, plus about 800-2000 L of water. This yields between 720-1800 L of sake.

Hatsu-zoe (First Addition)

The shubo is transferred to a larger tank where approximately 1/6 of the total amount of koji-mai, kake-mai, and water are combined. The temperature at this stage is typically between 54-59°F (12-15°C).

Odori (meaning to dance)

Nothing is added and yeast are allowed to propagate (dance).

Naka-zoe ("Middle")

Double the previous total amount of water, koji and steamed rice are added, so that the total volume at this stage is now about half the final total.

Tome-zoe

The remainder of the water, rice and koji are added. During the middle and final additions, because fermentation is exothermic, if the fermentation tank is not temperature-controlled via a water jacket, some brewers replace some of the added water with ice.

Ending the Fermentation

The temperature is lowered to 31-41 °F (3-5 °C) to stop the fermentation without killing the yeast, as dead yeast can produce off flavors.

Moromi Styles

Rich, high-umami styles like Futsu-shu and certain styles of Junmai:

Ginjo fermentation

Rich, high-umami styles like Futsu-shu and certain styles of Junmai:

- Typically,high-umami styles are made with rice of a 70% or higher polishing ratio to provide additional amino acids in fermentation.

- Fermentation also occurs at the top end of the temperature range which provide lower kasu ratios.

- In general, warmer fermentation temperatures result in more rapid ferments and create fuller-bodied sake with rice/cereal and spice/earthy flavors.

Ginjo fermentation

- The required fermentation temperatures of 46-54 °F (8-12°C) can last for as long as 30 to 35 days.

- Low fermentation temperatures keep the yeast activity in balance with the slow production of sugar as well as enhance the production of esters.

- Colder fermentation temperatures result in a slower fermentation that produces lighter-bodied and more floral/fruity flavors.

- Extremely cold fermentations are typically used in the production of ginjo, and result in green apple and banana flavors.

Finishing and Bottling

-

Additives

-

Filtration

-

Finishing

-

Aging

-

Blending/Bottling

<

>

Additives

Sake may be adjusted before filtration, but never after, with the exception of water. The permissible additives beyond more water, rice and koji are jozo alcohol, organics acids, amino acids, and sugar. The various additions are dictated by the style.

Jozo Alcohol

Jozo alcohol, a neutral spirit of 30% to 40% ABV, is added to increase the expression of aromas, as sake’s aromatic compounds are more soluble in alcohol than in water. Jozo alcohol usage creates a lighter palate profile and a shorter, cleaner finish, called kire. The extraction of aroma is especially ideal for the fruity esters created during ginjo fermentations.

The permissible quantities of jozo alcohol are as follows:

The fourth addition

To control the level of sweetness in some aruten sake, water and dissolved sugars, including small amounts of dextrins, are added. This is created by adding koji enzymes to a mix of steamed rice and water so that the rice starch is converted into sugar and residual dextrins.

Other additions for futsu-shu include:

Jozo Alcohol

Jozo alcohol, a neutral spirit of 30% to 40% ABV, is added to increase the expression of aromas, as sake’s aromatic compounds are more soluble in alcohol than in water. Jozo alcohol usage creates a lighter palate profile and a shorter, cleaner finish, called kire. The extraction of aroma is especially ideal for the fruity esters created during ginjo fermentations.

- If jozo alcohol is added, the sake is referred to as aruten, which is short for arukoru-tenka (alcohol addition), but this is not a labelling term. If no jozo alcohol is added, the sake is described as Junmai.

- Jozo alcohol, essentially vodka, (as it is distilled to over 95% ABV then proofed to 30% to 40% for storage and usage) was traditionally distilled from rice. Currently, it is common for Brazilian high proof molasses alcohol or grain alcohol to be used.

The permissible quantities of jozo alcohol are as follows:

- Premium non-junmai: 10%

- Futsu-shu 50% can be added.

- It should be noted: Jozo does not increase the final ABV therefore sake is not “fortified”

The fourth addition

To control the level of sweetness in some aruten sake, water and dissolved sugars, including small amounts of dextrins, are added. This is created by adding koji enzymes to a mix of steamed rice and water so that the rice starch is converted into sugar and residual dextrins.

Other additions for futsu-shu include:

- Glucose or other sugar adjust sweetness

- Organic acids adjust acidity.

- Umami may be added via permitted amino acids.

Filtration (of rice solids)

Seishu (清酒), is sake in which the solids have been strained out, leaving clear liquid. To separate the liquid from the rice solids, known as sake-kasu, one of the following techniques is employed:

Yabuta-Shibori (Assakuki)

Assakukui, though commonly referred to as Yabuta (the major manufacture of Assakuki), is an accordion-like machine with fabric pockets that are filled with the fermented porridge-like sake. Next to every sake filled pocket, there is an adjacent pocket that can be mechanically inflated with air. As the air pockets expand, they apply pressure to the adjacent sake-filled pockets, squeezing the liquid through the fabric while the fabric holds the solid sake-kasu. This is the industry standard method for Futsu-shu, Junmai and Honjozo. Many Ginjo and Daiginjo sake are now filtered this way, too.

Una-Shibori/Sase-shibori is the traditional method in which the fermented sake is poured into individual cloth bags made of a synthetic fabric or cotton. The bags are laid horizontally in a large wooden or metal tub called a fune. Pressure is then applied to each bag from above, which causes the sake to run out of the bags and then through a hole in the bottom of the tub while the solids remain inside the bag. As this pressure is typically lower pressure than yabuta-shibori, it typically results in a finer textured sake. The process takes approximately two days. Funa-shibori is typically used in the production of Ginjo styles of sake.

Fukuro-shibori (Drip Separation) is the traditional method in which the fermented sake is poured into 5L to 10L cloth bags. The cloth bags are then hung up to allow the liquid to drip through. Sake is collected in 18L (four-gallon) glass bottles called to-bin. As Fukuro-shibori only uses gravity and no mechanical pressure, it is a highly labor-intensive and time consuming process. This limits its use to super-premium sake like Daiginjo and Junmai Daiginjo, and competition sake. Sake produced using this method is sometimes called Shizuku-zake 雫酒 (drip sake). Post Fukuro-shibori process, some remaining liquid remains with the solids in the bags. The contents of the bags are typically filtered again using either Funa-shibori or Yabuta-shibori in order to ensure none of the liquid is wasted.

Funa-shibori and Fukuro-shibori expose the sake to air for an extended duration of time. This leads to increased oxidation.

Centrifuge Separation Centrifuge separation minimizes oxygen exposure and is currently used by a small number of breweries.

Nigorizake (濁り酒) (partially filtered sake)

Nogori-zake is filtered through a loose mesh which leaves a significant amount of rice lees in the bottle. The method was pioneered by a brewer in Kyoto in the 1960s after working with local legislators to work around sake's filtration requirement while still allowing lees to pass through.

Yabuta-Shibori (Assakuki)

Assakukui, though commonly referred to as Yabuta (the major manufacture of Assakuki), is an accordion-like machine with fabric pockets that are filled with the fermented porridge-like sake. Next to every sake filled pocket, there is an adjacent pocket that can be mechanically inflated with air. As the air pockets expand, they apply pressure to the adjacent sake-filled pockets, squeezing the liquid through the fabric while the fabric holds the solid sake-kasu. This is the industry standard method for Futsu-shu, Junmai and Honjozo. Many Ginjo and Daiginjo sake are now filtered this way, too.

Una-Shibori/Sase-shibori is the traditional method in which the fermented sake is poured into individual cloth bags made of a synthetic fabric or cotton. The bags are laid horizontally in a large wooden or metal tub called a fune. Pressure is then applied to each bag from above, which causes the sake to run out of the bags and then through a hole in the bottom of the tub while the solids remain inside the bag. As this pressure is typically lower pressure than yabuta-shibori, it typically results in a finer textured sake. The process takes approximately two days. Funa-shibori is typically used in the production of Ginjo styles of sake.

Fukuro-shibori (Drip Separation) is the traditional method in which the fermented sake is poured into 5L to 10L cloth bags. The cloth bags are then hung up to allow the liquid to drip through. Sake is collected in 18L (four-gallon) glass bottles called to-bin. As Fukuro-shibori only uses gravity and no mechanical pressure, it is a highly labor-intensive and time consuming process. This limits its use to super-premium sake like Daiginjo and Junmai Daiginjo, and competition sake. Sake produced using this method is sometimes called Shizuku-zake 雫酒 (drip sake). Post Fukuro-shibori process, some remaining liquid remains with the solids in the bags. The contents of the bags are typically filtered again using either Funa-shibori or Yabuta-shibori in order to ensure none of the liquid is wasted.

Funa-shibori and Fukuro-shibori expose the sake to air for an extended duration of time. This leads to increased oxidation.

Centrifuge Separation Centrifuge separation minimizes oxygen exposure and is currently used by a small number of breweries.

Nigorizake (濁り酒) (partially filtered sake)

Nogori-zake is filtered through a loose mesh which leaves a significant amount of rice lees in the bottle. The method was pioneered by a brewer in Kyoto in the 1960s after working with local legislators to work around sake's filtration requirement while still allowing lees to pass through.

- As Japanese legislation requires sake to be filtered, calling Nigori “unfiltered sake,” is incorrect.

- As in most sake, Nigori-zake is a descriptor of a process rather than an overall style. This means that rice polishing rates vary as well as the usage of jozo alcohol. There can even be Nama or sparkling Nigori-zake.

- Due to the sake lees, Nigori-zake has a shorter shelf life than clear sake. If the flavors degrade, the lees can develop orange, brown or greyish colors.

- Before serving, the bottle is shaken to mix the sediment and turn the sake white or cloudy.

Nigori-zake styles:

Filtration of Fractions

Like in fractional distillation, a sake’s flavors differ based upon when the sake leaves the filter. The different fractions are:

Arabashiri (Free-run Sake):

The first part of the sake that comes off the moromi when pressed contains few particles and has a relatively lower ABV. As it comes off the press first, it is freshly fermented and can still contain carbon dioxide. Some breweries release this type of sake as unmatured, unpasteurised, and seasonal to maximise its freshness. If the arabashiri is bottled with the other fractions, it is blended as a component in less expensive sake.

Naka-dori/Naka-gumi (Middle Fraction):

Seme (Final fraction)

Seme is the final, fraction that is more coarse in texture. Seme is the final, fraction that is more coarse in texture. Typically, it is also less aromatic because it has more exposure to oxygen and increased contact with the lees. If a Funa-shibori is being used, pressure is increased, which may cause proteins, lipids and unconverted starch fragments to be extracted from the sake-kasu. This may result in bitter flavors, astringency and a coarse texture. In a fune, it is common to rearrange the bags to press and extract a little more liquid through another filtration.

Residual solids

Sake-kasu is the solid cake left over from the filtration process. It contains 8% ABV and can be eaten, used for shochu, or for cooking and pickling vegetables.

- Usu-nigori: Thick lees make the sake richly textured and full-bodied with a higher acidity content.

- Sasa-nigori: This sake contains the least amount of residual lees relative to other nigori. The remaining lees give some texture to the sake.

- Kassei-nigori: This sake entered a second fermentation, creating gas in the bottle just like champagne.

Filtration of Fractions

Like in fractional distillation, a sake’s flavors differ based upon when the sake leaves the filter. The different fractions are:

Arabashiri (Free-run Sake):

The first part of the sake that comes off the moromi when pressed contains few particles and has a relatively lower ABV. As it comes off the press first, it is freshly fermented and can still contain carbon dioxide. Some breweries release this type of sake as unmatured, unpasteurised, and seasonal to maximise its freshness. If the arabashiri is bottled with the other fractions, it is blended as a component in less expensive sake.

Naka-dori/Naka-gumi (Middle Fraction):

- The middle fraction of Funa-shibori sake can be labelled as Naka-dori or Naka-gumi, but there is no legal definition. It is the brewer’s decision as to where the cut is made. Naka-dori produces the sake with a silky texture.

Seme (Final fraction)

Seme is the final, fraction that is more coarse in texture. Seme is the final, fraction that is more coarse in texture. Typically, it is also less aromatic because it has more exposure to oxygen and increased contact with the lees. If a Funa-shibori is being used, pressure is increased, which may cause proteins, lipids and unconverted starch fragments to be extracted from the sake-kasu. This may result in bitter flavors, astringency and a coarse texture. In a fune, it is common to rearrange the bags to press and extract a little more liquid through another filtration.

Residual solids

Sake-kasu is the solid cake left over from the filtration process. It contains 8% ABV and can be eaten, used for shochu, or for cooking and pickling vegetables.

Finishing

Sedimentation

To remove any sediment and color after filtration, the following techniques may be used:

Raka (Charcoal filtering) Activated

carbon/charcoal may be added to remove undesirable aromas, flavors, and textures. This is typically added in the form of a powder, and then filtered out. The practice dates back to between 1911 and 1923, and was used in competition sake. It became popular with the development of light, crisp, dry, water-white Niigata sake of the 1980’s. Raka also slows the development of color and aged aromas.

Pasteurization (Hi-ire)

Most sake is typically pasteurized twice to stop bottle fermentation by both koji and lactic acid bacteria called hi-ochi kin. On both occasions, the sake is heated to a temperature of 140-149°F (60-65 °C). This is done immediately after filtration (before storage) and a second time before being shipped out (after storage). Technically, these microbes could be filtered out in lieu of pasteurization; however, the equipment is cost prohibitive to all but some large breweries.

To remove any sediment and color after filtration, the following techniques may be used:

- Settling

- Protein Fining

Raka (Charcoal filtering) Activated

carbon/charcoal may be added to remove undesirable aromas, flavors, and textures. This is typically added in the form of a powder, and then filtered out. The practice dates back to between 1911 and 1923, and was used in competition sake. It became popular with the development of light, crisp, dry, water-white Niigata sake of the 1980’s. Raka also slows the development of color and aged aromas.

- Muroka (無濾過) is a sake that was not charcoal filtered.

Pasteurization (Hi-ire)

Most sake is typically pasteurized twice to stop bottle fermentation by both koji and lactic acid bacteria called hi-ochi kin. On both occasions, the sake is heated to a temperature of 140-149°F (60-65 °C). This is done immediately after filtration (before storage) and a second time before being shipped out (after storage). Technically, these microbes could be filtered out in lieu of pasteurization; however, the equipment is cost prohibitive to all but some large breweries.

- Ja-kan method (Bulk pasteurization)

Aging

Koshu (古酒) sake typically refers to sake that has been matured for two years or more in stainless steel. This type of sake typically has higher levels of sugar and acidity which is created by using a type of so-haze that produces a thicker than usual koji. This high quantity of koji expedites the starch-to-sugar enzymatic activity. It is also common to add acid during the sake-making to balance the sweetness and intensity of the final flavors. Blending enables the brewer to control the flavor profiles in order to maintain consistency. Some brewers blend different styles and vintages, resulting in sake that turns yellow and acquires a honeyed flavor.

Kijoshu (Noble Ferment sake) is akin to noble-rot wine. In the production of kijoshu, part of the water typically used in the moromi is replaced with sake. Typically, this substitution happens on the fourth day. The sake that is added to the moromi is of the same grade as the kijoshu that is being made. Any grade of sake can be made in a Kijoshu style, but most have a polishing ratio between 60 and 70 percent. The brewing process for kijoshu was invented in 1973 by Dr. Makoto Sato at the National Research Institute of Brewing (NRIB).

Taru-zake (樽酒)

Historically, sake was stored in casks of sugi (杉 Japanese cedar) while being transported. To recreate the effect, sake of Honjozo, Junmai and Futsu-shu are stored in barrels of 72 L (though 36-litre and 18-litre barrels are also used) for one to two weeks before blending for flavor consistency. Sake casks are often tapped ceremonially for the opening of buildings, businesses, and parties.

Sparkling Sake (Happ-oshu)

Sparkling sake originated in the 1990’s with both force-carbonated and bottle-fermented sake. Currently, the production method of sparkling sake is not defined or regulated and no standard label terms exist. However, there are common production methods for sparking sake which are:

Genshu (原酒) is undiluted sake. Most sake is diluted with water after brewing to lower the alcohol content from 18–20% down to 14–16%, but genshu is not.

Koshu (古酒) sake typically refers to sake that has been matured for two years or more in stainless steel. This type of sake typically has higher levels of sugar and acidity which is created by using a type of so-haze that produces a thicker than usual koji. This high quantity of koji expedites the starch-to-sugar enzymatic activity. It is also common to add acid during the sake-making to balance the sweetness and intensity of the final flavors. Blending enables the brewer to control the flavor profiles in order to maintain consistency. Some brewers blend different styles and vintages, resulting in sake that turns yellow and acquires a honeyed flavor.

Kijoshu (Noble Ferment sake) is akin to noble-rot wine. In the production of kijoshu, part of the water typically used in the moromi is replaced with sake. Typically, this substitution happens on the fourth day. The sake that is added to the moromi is of the same grade as the kijoshu that is being made. Any grade of sake can be made in a Kijoshu style, but most have a polishing ratio between 60 and 70 percent. The brewing process for kijoshu was invented in 1973 by Dr. Makoto Sato at the National Research Institute of Brewing (NRIB).

Taru-zake (樽酒)

Historically, sake was stored in casks of sugi (杉 Japanese cedar) while being transported. To recreate the effect, sake of Honjozo, Junmai and Futsu-shu are stored in barrels of 72 L (though 36-litre and 18-litre barrels are also used) for one to two weeks before blending for flavor consistency. Sake casks are often tapped ceremonially for the opening of buildings, businesses, and parties.

- Sugi casks transfer flavor quickly therefore aging is short.

- Ginjo styles are not typically used because the delicate aromas are overwhelmed by the wood.

- The sake must be stored in cedar vats. Planks, chips, and other types of wood may not be used to provide wood flavor.

- Sugi casks are each used three times before being discarded.

Sparkling Sake (Happ-oshu)

Sparkling sake originated in the 1990’s with both force-carbonated and bottle-fermented sake. Currently, the production method of sparkling sake is not defined or regulated and no standard label terms exist. However, there are common production methods for sparking sake which are:

- Force Carbonated Sake

- Bottle Fermented Bottle-fermented sparkling sake is initially made the same way as regular sake, but fermentation is stopped at 5- 10% ABV, as opposed to the 18-20% abv of normal sake. The sake is then filtered and bottled. Within the bottle, fermentation continues and produces carbonation, as well as adding an extra 1-1.5% abv. It is not common to disgorge (remove the yeast from) this style of sparkling sake because sake yeast do not flocculate (clump together). Because is this, most of the sake made with this method is sold as “nama”

- Live Nigori

- Wari-mizu (Dilution)

Genshu (原酒) is undiluted sake. Most sake is diluted with water after brewing to lower the alcohol content from 18–20% down to 14–16%, but genshu is not.

Blending

Blending is used to mix sake with different components. For example:

Bottling

The glass chosen for sake is critical because it helps protect the delicate aromas and flavors from light damage. Similar to beer:

Other Labeling Terms

Nihonshu-do (Sake Meter Value/SMV) measures the density of sake compared to water. The higher the SMV, the dryer sake, and there is less residual sugar. The lower the SMV, the sweeter the sake due to the higher amount of residual sugar.

San-do (Acidity) is the number of milliliters of liquid sodium hydroxide needed to neutralize ten milliliters of sake. High acidity lightens flavors and minimizes perceived sweetness. Conversely, low acidity will be perceived as fuller and heavier with an increased sense of sweetness.

Amino Acids Level typically range from 1.0 to 2.0 with a higher number meaning more umami.

Blending is used to mix sake with different components. For example:

- Different polishing ratios (The blending component with the highest polishing ratio limits the sake grade.)

- Different rice types or yeast types

- Different press fractions

- Different ages

- Different storage methods

- Different amounts of sake lees (for nigori-zake only}

Bottling

The glass chosen for sake is critical because it helps protect the delicate aromas and flavors from light damage. Similar to beer:

- Brown bottles: provide the most protection.

- Green bottles: provide some protection.

- Clear bottles: provide: no protection.

Other Labeling Terms

Nihonshu-do (Sake Meter Value/SMV) measures the density of sake compared to water. The higher the SMV, the dryer sake, and there is less residual sugar. The lower the SMV, the sweeter the sake due to the higher amount of residual sugar.

San-do (Acidity) is the number of milliliters of liquid sodium hydroxide needed to neutralize ten milliliters of sake. High acidity lightens flavors and minimizes perceived sweetness. Conversely, low acidity will be perceived as fuller and heavier with an increased sense of sweetness.

Amino Acids Level typically range from 1.0 to 2.0 with a higher number meaning more umami.

Flavors of Sake

The flavors of sake are typically discussed as having a taste that is light or rich and an aroma that is fragrant or subtle. Though it is common to refer the Tokutei Meisho-shu designations to discuss flavor and style, as generalizations do exist, this was not the objective for implementation. Instead Tokutei Meisho-shu designations were derived for taxation purposes, as the previous approach to taxation favored larger breweries and put small breweries at a disadvantage.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Service and Storage

-

Storage

-

Service

-

Beverage Program Implimentation

<

>

Storage

Aging/Shelf Life: Consumed within 1 year of being released by the brewery.

Storage Temperature: Ideal: 41° F (5° C) which is the temperature at which sake is generally rested at. For short term storage, at least 59°F (15° C).

Storage Position: Sake should be stored upright.

After opening: 1-2 weeks Sake’s flavors degrade predominantly due to the dissipation of aromas rather than oxidization, like in wine. For this reason, vacuum preservation is not ideal.

Aging/Shelf Life: Consumed within 1 year of being released by the brewery.

Storage Temperature: Ideal: 41° F (5° C) which is the temperature at which sake is generally rested at. For short term storage, at least 59°F (15° C).

Storage Position: Sake should be stored upright.

After opening: 1-2 weeks Sake’s flavors degrade predominantly due to the dissipation of aromas rather than oxidization, like in wine. For this reason, vacuum preservation is not ideal.

Heating Sake

Sake is heated in tokkuri (ceramic decanter) which is then placed in a pot of hot water.

Serving Glass

Sake is heated in tokkuri (ceramic decanter) which is then placed in a pot of hot water.

Serving Glass

- Aromatic Sake: Ideally served in a white wine glass. It can also be served in a sakazuki (ceramic sake cup) with a wide mouth.

- Rich Sake (in particular Junmai and Honjozo): Ceramic sake cup if warm

- Aged sake: Brandy Snifter

- Sparkling Sake: Champagne glass

Service

Serving Temperature

Serving Temperature

- Reishu: 41 - 50 °F (5-10° C)

This temperature may mask subtle flavors. - Shitsu-on: 68°F (20°C)

Ideal temperature for the preservation of a sake’s aroma and flavor.

- Nuru-kan 104°F (40°C)At this temperature, a sake’s aroma and flavor seem richer and fuller.

- Jho-kan: 113°F (45°C) Aromas are concentrated and flavors feel soft and crisp

- Atsu-kan: 122F (50°C) Sake aromas are sharp and dry with a clean finish.

Figuring out which sake to carry can be complex. Unlike beer or wine, categories are significantly broader, and styles can have overlapping flavor and aroma characteristics. Keith Nakaganeku, Cherry Company’s Sales Supervisor and Certified Sake Sommelier, provided this

insight into purchasing sake as a corporate buyer.

1. What does your customer want from a sake selection?

“Ultimately if you want to sell the sake, I think you have to look at it from that angle of ‘What is your clientele wanting?’" said Keith. “To figure this out, the next question should be: ‘Who are my guests, who is my target demographic?’”

What your customers want from a sake menu can include:

A few offerings to round out a beverage menu or retail selection.

A range of sake to compliment the food on the menu.

An extensive menu to showcase the multitude of flavors across the entire sake spectrum.

Local vs Visitor Tastes

The tastes of U.S. mainland tourists, Japanese tourists and local kamaʻaina are very different.

Locals

“If you're not Japanese-centric in your food, and you're adding sake to your menu, I would ask the rep for three to four top-selling jizake [artisan craft sake] with brands people recognize. Obviously, [if regular guests ask for something specific] you might want to make sure to carry that sake.

U.S. Mainland Tourists

“The sake boom in the United States is still going strong. People are still interested in sake. When they come to Hawaiʻi and hear that sake is on the menu, a lot of times they're going to order sake. It doesn't have to be jizake, it could be [a Japanese] national brand sake. It doesn't matter, [to them] sake is sake. In that [case], you could ask the rep, "What are some of the popular national brands and popular jizake?" I would also make sure to include a nigori [unfiltered] sake. What I find is that most of the mainland tourists like to have nigori sake. You also want a sparkling sake.

“I would also really consider hot sake. [In particular] if you have a sushi bar in a hotel, or an Asian-themed restaurant in a hotel or some place in Waikīkī. Traditionally, people always thought sake was supposed to be hot. Only recently have we introduced premium sake cold. Now, sometimes but not always, people associate cold sake with better quality. [However,] I think that people still gravitate towards hot sake because of price point.

2. How much storage space is available?

Ideally, sake should be kept refrigerated, although it should always be stored below 70° F to prevent flavor degradation. Cherry Co, for example, keeps sake chilled at their warehouse. Some kura [sake breweries] require the sake to be kept refrigerated at all times at the establishments they distribute to. It should be noted that refrigeration space for 1.8L bottles can be an issue due to the taller height of a sake bottle versus a standard wine bottle.

Off-premise

Retailers should first consider floor space and refrigeration options. If refrigeration is not required, where will sake be stored? In-store, dry-shelf storage is fine, assuming the store is always kept below 70° F.

On-premise

Similar to wine, once opened, there is a best-by life of approximately one week before flavors degrade. Beyond estimating refrigeration space for sake, the volume of sake that moves should also be taken into account.

3. How many products to carry?

The results of the first two questions should yield the approximate number of different products to carry.

4. What is the service set-up?

“As the price of the sake goes up, your level of interaction with the customer needs to go up,” said Keith. This is a universal truth in sales: The more expensive a product is, the more customer service is required to sell the product. This goes for both on and off-premise sales. It is essential to take into account the amount of training that the servers or sales team will require in order to understand how to guide the customer through sake.

The first place to start training would be to have your team read the Guide to Sake available at hawaiibevguide.com/sake. Adding on a staff sake training, which a company like Cherry Co can assist with, is another great way to educate your staff. In order to efficiently sell the product, it helps to know the sake’s story, as well as the relevant facts and figures.

Off-premise

If the goal is to round out the offerings, rather than being a specialty establishment that will be offering customers product insight, then carrying best-sellers may be a good approach.

On-Premise

Estimating sake sales is essential to figuring out proper storage space. Though sake will not spoil, the taste will change over time. Consumption within 1 week of opening is ideal. This oxidation is why the same bottle of sake can taste great at one place, but not as good at another. To minimize the duration of time a bottle is open, different sized bottles are sold. The most common sizes are: 200ml cup, 300ml, 720ml (most common size bottle), and 1.8L.

Keith noted, “The current trend is to move away from the 1.8L bottles and move to the 300ml bottle as a single serving.” The movement to a smaller bottle allows guests to serve themselves. The smaller the bottle, however, has a higher the cost per ml because of economies of scale. Sizes available vary by product. Many products have multiple sizes.

Hot Sake Program

A hot sake program can be executed in a multitude of ways:

A hot water bath is traditional. However, the counter space and labor for a hot water bath may be limiting. One option would be to use an immersion circulator for a consistent temperature to minimize the risk of overheating the sake.

50-liter box of sake, with a sake warmer. This approach requires the least amount of labor as the box is elevated and sake is run through a heated pipe. It also provides the most instantaneous customer experience, as a hot water bath can take 15 minutes. The machines cost $1,000 to $1,500, but, according to Keith, the payback period can be quick because “you can go through quite a bit of sake this way”. Cherry Co, or another distributor, can help with the purchasing of a hot sake warmer.

Microwaving sake in a tokkuri is regularly practiced but not recommended, as it can agitate the flavor molecules more than is ideal.

Glassware

Glassware's space requirements needs to be taken into account. If cold sake will be served in wine glasses, which may be ideal from both a flavor and space standpoint, then no additional consideration is needed. If sake is served from tokkuri and sake cups, the cost per unit is minimal, but additional storage space for cups is required. “I find that most places that are starting up a sake program are really resistant to using wine glasses, although I try to encourage them to use a wine glass for premium sake. I think it's just the aesthetic look of a wine glass that doesn't match with the stereotypical thought of what sake should be served in,” said Keith.

Additionally, portion size will dictate pour cost and bottle size. “Let's say you serve sake in a 2-ounce shot glass or a small sake glass. You're going to get about 12 pours out of a 720ml bottle. If you use a larger sake glass or wine glass, where you can put about 4 ounces of sake, you're going to get six pours out of a 720ml bottle. That's going to adjust your pricing per pour. Then, if you want to run a program that uses a masu [sake box] that's about six ounces per pour. If you're going to do that, then you might as well go with the 1.8Lbottle because you're only going to get about two pours out of a 720ml bottle. Now, you've got to think about, "Well, if I'm going to pour like this, what am I going to have to charge for this, in order to make a decent profit?" [Even if the by-the-ounce price is comparable] are people going to pay $35 for a ‘glass of sake’, even if it is six ounces? Versus another restaurant which, for the same sake, only charged $24 for a four-ounce pour. The customer doesn't think about the portion size [at that point], normally. The customer just says, "This place is really expensive for sake.

Selecting Individual Bottles

Price Point

Sake, from a price and overall service standpoint, is similar to wine. The sky's the limit with price, and once a bottle is open, it has a shelf life. With that said, one can approach sake from a price standpoint like they would a by-the-glass wine menu. Expect $6 -$10 for the lower end and 15-$20 per glass on the high end.

Sake Meter Value (SMV) and Acidity (Dry vs Sweet)

“People are split on whether they like sweeter sake or dryer sake. I found that most people are on the dryer sake side.” Generally, Keith recommends 20% of the sake options being of a sweeter style of sake with a Sake Meter Value (SMV) of (greater than) >2.0 and 80% of the selection a dryer style of sake SMV of (less than) <1.0. He also noted that SMV can be misleading in perceived sweetness, as acidity also plays a role. If two sake have the same SMV, the one with higher acidity will be perceived as dryer.

Sake by Flavor

Off-Premise

Once a concept is chosen, then a sales rep should be able to help choose the best-selling items within the general style and flavor categories.

On-Premise

In building a unique program, there are restaurant-specific sake that cannot be sold by retailers. Beyond this, other on-premise approaches to help decipher what specific sake to include on a menu are:

Building a Sake Flight

For a program that may not be known for sake, a sake flight is a great way to introduce guests to the product without them having to commit to a whole bottle. Keith recommended the following approach to building a sake flight of three 2-oz pours. “You want to have contrast in flavors, and you want a contrast in price points. [From a flavor perspective], you can pair a soushu sake, a kunshu sake, and a junshu. Or you can do two soushu or two kunshu. Then, look at price point contrast and you have a lower price point, medium price point, then higher price point sake.”

Food pairing

Japan, being a country of islands, has a cuisine that is seafood-centric. Instead of only thinking about pairing sake to Japanese food, think about sake as a great pairing for seafood in general. A study by the National Research Institute of Brewing in Hiroshima, which was published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry found that “an undesirable taste and fishy off-odor appeared to be caused by degradation of unsaturated fatty acids (e.g., docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)), which are found in fish and squid.” 1 Sake, however, does not have this effect on fish and seafood.

“One place that I think underutilizes sake is raw bars [with] oysters, and that type of stuff,” Keith said. “I think that sake is one of the best pairings out of any liquor if you're going to serve raw oysters.” This is not to say that sake cannot be paired with other styles of food.

Specialty Concept Pairing

Craft Beer Bar Recommendation